by PRIDE Reading Program Admin | Mar 20, 2018 | A PRIDE Post, PRIDE Reading Program, Reading Skills

The Kindergarten school year is coming to an end and as a parent your thoughts are probably turning towards first grade. Is your child ready for first grade reading? How do you know? Here is a list of benchmark reading accomplishments for kindergarten that was included in a report prepared by a National Academy of Sciences panel titled Preventing Reading difficulties in Young Children, Catherine E. Snow. Kindergarten Reading Benchmarks.

Your Child…

Has reached the reading benchmarks for Kindergarten if he or she:

- Knows the parts of a book and their functions.

- Begins to track print when listening to a familiar text being read or when rereading own writing.

- “Reads” familiar texts emergently, i.e., not necessarily verbatim from the print alone.

- Recognizes and can name all uppercase and lowercase letters.

- Understands that the sequence of letters in a written word represents the sequence of sounds (phonemes) in a spoken word (alphabetic principle).

- Learns many, though not all, one-to-one letter-sound correspondences.

- Recognizes some words by sight, including a few very common ones (a, the, I, my, you, is, are).

- Uses new vocabulary and grammatical constructions in own speech.

- Makes appropriate switches from oral to written language situations.

- Notices when simple sentences fail to make sense.

- Connects information and events in texts to life, and life to text experiences.

- Retells, reenacts, or dramatizes stories or parts of stories.

- Listens attentively to books teacher reads to class.

- Can name some book titles and authors.

- Demonstrates familiarity with a number of types or genres of text (e.g., storybooks, expository texts, poems, newspapers, and everyday print such as signs, notices, labels).

- Correctly answers questions about stories read aloud.

- Makes predictions based on illustrations or portions of stories.

- Demonstrates understanding that spoken words consist of a sequence of phonemes.

- Given spoken sets like “dan, dan, den,” can identify the first two as being the same and the third as different.

- Given spoken sets like “dak, pat, zen,” can identify the first two as sharing a same sound.

- Given spoken segments, can merge them into a meaningful target word.

- Given a spoken word, can produce another word that rhymes with it.

- Independently writes many uppercase and lowercase letters.

- Uses phonemic awareness and letter knowledge to spell independently (invented or creative spelling).

- Writes (unconventionally) to express own meaning.

- Builds a repertoire of some conventionally spelled words.

- Shows awareness of distinction between “kid writing” and conventional orthography.

- Writes own name (first and last) and the first names of some friends or classmates.

- Can write most letters and some words when they are dictated.

Has your child NOT reached these reading benchmarks for Kindergarten?

If you are worried that your child did not reach the reading benchmarks for Kindergarten, keep in mind that about 80% of kids learn to read and write with very little instruction. The other 20% do not learn that way. They need things to be broken down and need to be taught. This 20 percent needs early intervention. With intensive instruction, your child can get on track. If you are in need of a really great reading intervention program, please check out the PRIDE Reading Program here.

Thank you for reading my post today!

Karina Richland, M.A., is the author of the PRIDE Reading Program, a multisensory Orton-Gillingham reading, writing and comprehension curriculum that is available worldwide for parents, tutors, teachers and homeschoolers of struggling readers. Karina has an extensive background in working with students of all ages and various learning modalities. She has spent many years researching learning differences and differentiated teaching practices. You can reach her @ info@pridereadingprogram.com or visit the website at www.pridereadingprogram.com

by PRIDE Reading Program Admin | Jan 16, 2018 | A PRIDE Post, Dyslexia, Multisensory Teaching, Orton-Gillingham

Learning to read in English would be so easy for kids with Dyslexia if all similar-sounds were spelled the same. They aren’t. English is so hard to learn and has so many unfair and horrible spelling rules! Ugggh!

Many of us just read naturally. We understand that letters and letter combinations create words and sounds. Our brains just naturally register the words in print and we can read three or four words ahead of time and visually scan an entire text. We are also mentally able to pull words apart, separate them into syllables and apply all of those horribly unfair spelling rules easily and logically.

In the beginning…

Reading is complicated. There are 3 major stages that a child will need to go through in their lifetime to become a strong reader. This process involves word recognition, comprehension, fluency, and most importantly… motivation. The following outlines the key features of the reading process at each stage:

Stage 1 of the Reading Process: Decoding (Ages 6-7)

At this stage, beginning readers learn to decode by sounding out words. They comprehend that letters and letter combinations represent sounds and use this information to blend together simple words such as hat or dog.

Stage 2 of the Reading Process: Fluency (Ages 7-8)

Once children have mastered the decoding skills of reading, they begin to develop fluency and other strategies to increase meaning from print. These children are ready to read without sounding everything out. They begin to recognize whole words by their visual image and orthographic knowledge. They identify familiar patterns and achieve automaticity in word recognition and increase fluency as they practice reading recognizable texts.

Stage 3 or the Reading Process: Comprehension (Ages 8-14)

Stage 3 or the Reading Process: Comprehension (Ages 8-14)

Children in this stage have mastered the reading process and are able to sound out unfamiliar words and read with fluency. Now the child is ready to use reading as a tool to acquire new knowledge and understanding. During this stage, vocabulary, prior knowledge, and strategic information become of utmost importance. Children will need to have the ability to understand sentences, paragraphs, and chapters as they read through text. Reading instruction during this phase includes the study of word morphology, roots, prefixes as well as a number of strategies to help reading comprehension and understanding.

Let’s keep it simple…

I’m not going to get too deep into the semantics of each reading phase and how it all works but Dr. G. Reid Lyon, a researcher in the field of neurology of dyslexia wrote a great article on children and the process of reading if you want to read it here.

So…now that you understand that there is a natural progression to reading, the big question is, will a child with dyslexia eventually learn to read naturally as they mature….

Will the reading come naturally for a dyslexic child at some point?

Nope. Reading does NOT and never will come naturally for a dyslexic child. A child with dyslexia does not wake up one morning and say, “I get it mom, it all makes sense now!” Nope. Unfortunately this isn’t going to happen.

This is just a fact. The International Dyslexia Association has a really good fact sheet on Dyslexia and the Brain. You can read about it here.

Children with dyslexia read and spell everything phonetically and do not apply spelling rules. For example, if they are spelling the word “said“ they will write “sed.” When reading the word “horse,” the dyslexic child will make a mental picture of that word and every time he or she approaches the word “horse” in text, that mental picture comes to life. The problem with this strategy is that when they get to a word that they are unfamiliar with, they have no coping mechanisms to attack that particular word. Yikes!

There is GREAT news for kids with Dyslexia!!!

Even though the reading and spelling does not come naturally for a child with dyslexia, this does not mean that they can’t learn to read and spell. Kids with Dyslexia are really bright kids, that just need a different approach to reading and spelling. They need to learn the letters and letter combinations in a very very structured, systematic and cumulative approach. They need lots of repetition and practice and they need a lot of positive encouragement. Children with dyslexia need 3 crucial elements to their reading instruction:

Multisensory Teaching

Orton-Gillingham Program

Parent Support

What does multisensory mean?

See it – Say it – Hear it – Move with it!

When taught with a multi-sensory approach, children will learn all the letters, letter combinations, sounds and words by using all of their pathways – hearing (auditory), seeing (visual), touching (tactile) and moving (kinesthetic).

When learning the vowel combination ‘oa,’ for example, the child might first look at the letter combination on a picture of a GOAT, then close his/her eyes and listen to the sound, then trace the letters in the air while speaking out loud. This combination of listening, looking, and moving around creates a lasting impression for the child as things will connect to each other and become memorable. Using a multi-sensory approach to reading will benefit ALL learners, not just those with dyslexia.

When learning the vowel combination ‘oa,’ for example, the child might first look at the letter combination on a picture of a GOAT, then close his/her eyes and listen to the sound, then trace the letters in the air while speaking out loud. This combination of listening, looking, and moving around creates a lasting impression for the child as things will connect to each other and become memorable. Using a multi-sensory approach to reading will benefit ALL learners, not just those with dyslexia.

What is Orton-Gillingham?

The other significant component in helping a child with dyslexia learn to read and spell is utilizing an Orton-Gillingham approach. In Orton-Gillingham, the sounds are introduced in a systematic, sequential and cumulative process. The Orton-Gillingham teacher, tutor or parent begins with the most basic elements of the English language. Using lots of different multisensory strategies and lots of repetition, each spelling rule is taught one at a time. By presenting one rule at a time and practicing it until the child can apply it with automaticity and fluency, a child with dyslexia will have no reading gaps in their reading and spelling skills.

Children are also taught how to listen to words or syllables and break them into individual sounds. They also take each individual sounds and blend them into a words, change the sounds in the words, delete sounds, and compare sounds. For example, “…in the word steak, what is the first sound you hear? What is the vowel combination you hear? What is the last sound you hear? Children are also taught to recognize and manipulate these sounds. “…what sound does the ‘ea’ make in the word steak? Say steak. Say steak again but instead of the ‘st’ say ‘br.’- BREAK!

Every lesson the student learns in Orton-Gillingham is in a structured and orderly fashion. The child is taught a skill and doesn’t progress to the next skill until the current skill is mastered. Orton-Gillingham is extremely repetitive. As the children learn new material, they continue to review old material until it is stored into the child’s long-term memory.

It is like learning a foreign language.

Kids with Dyslexia need more structure and repetition in their reading instruction. They need to learn basic language sounds and the letters that make them, starting from the very beginning and moving forward in a gradual step by step process. Think of it as if your child is learning a foreign language for the first time. He or she needs to start at the very beginning, learn the pronunciation of each letter in the alphabet as well as all the different spelling and language rules related to the foreign language. This needs to be delivered in a systematic, sequential and cumulative approach. For all of this to “stick” the child will need to do this by using their eyes, ears, voices, and hands.

If you want to learn more about an Orton-Gillingham Dyslexia Reading Program click on the video below:

If you enjoyed reading this post, you might also enjoy reading, My child might have Dyslexia… what do I do?

Thank you so much for visiting my Blog today!

Karina Richland, M.A., developed the PRIDE Reading Program, an Orton-Gillingham program for struggling readers, based on her extensive experience working with children with learning differences over the past 30 years. She has been a teacher, educational consultant and the Executive Director of PRIDE Learning Centers in Southern California. Please feel free to email her with any questions at info@pridelearningcenter.com. Visit the PRIDE Reading Program website at https://www.pridereadingprogram.com

by PRIDE Reading Program Admin | Nov 6, 2017 | A PRIDE Post, Phonological Awareness, Reading Skills

To be ready to read, a child not only needs to know the letters of the alphabet but also must be aware that his or her own speech is made up of segments that differ from letters. These segments are called phonemes. I will try not to use too much teacher jargon in this blog, but this term is worth learning because it is critical to understanding reading and phonemic awareness. Without phonemic awareness, a child cannot read.

What is Phonemic Awareness

Phonemic awareness is the ability to identify and manipulate the individual speech sounds into spoken words. For example the word cat has three sounds – /c/, /ă/ and /t/. The word heat also has three sound /h/, /ē/, /t/ because the letters ea make one sound. Words can be divided into several other units such as syllables and rhymes. The smallest unit of sound in our language is a phoneme and there are forty four of them!

Phonemes do not correspond one-to-one with letters because some sounds are represented with two letters, like sh, ch, th and ng. The awareness of the separate sounds in a word is what we call phonemic awareness. It is an auditory skill that underlies the ability to use an alphabet to read and write. A child who can recognize that the word cat has three speech sounds, the word eye has one, and the word eat has two, possesses basic phonemic awareness.

If a child can change the /m/ sound at the beginning of the word mat to /r/ and know that the word is now rat, has demonstrated an even larger degree of phonemic awareness. This child can compare the sounds in words, substitute a new sound for an old one, and blend the sounds to make a new word.

Phonemic Awareness Activities

When I developed the PRIDE Reading Program, I made extra sure that every single lesson and skill the students learn also include phonemic awareness activities. A few examples of what the students have to do in the PRIDE Reading Program:

Identify rhymes – “tell me all of the words you know that rhyme with the word “heel.”

Listening for sounds – “close your eyes as I read some words to you. When you hear the “ū” sound, raise your hand.”

Manipulating sounds in words by adding, deleting or substituting – “in the word LAND, change the L to H.” (hand)

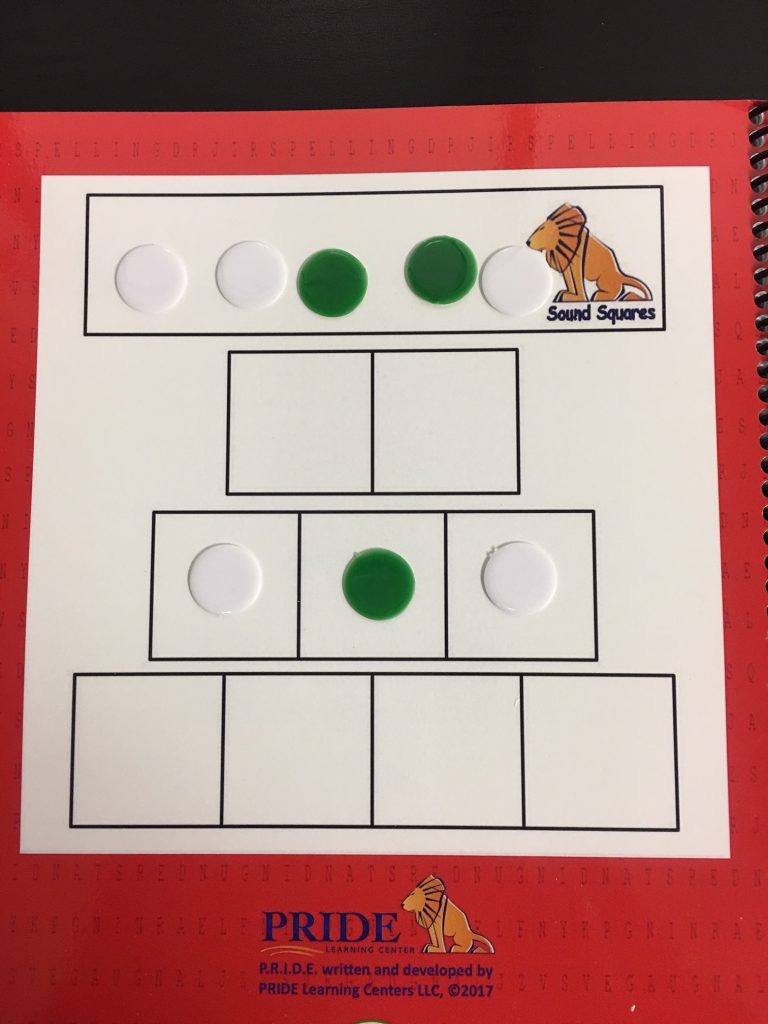

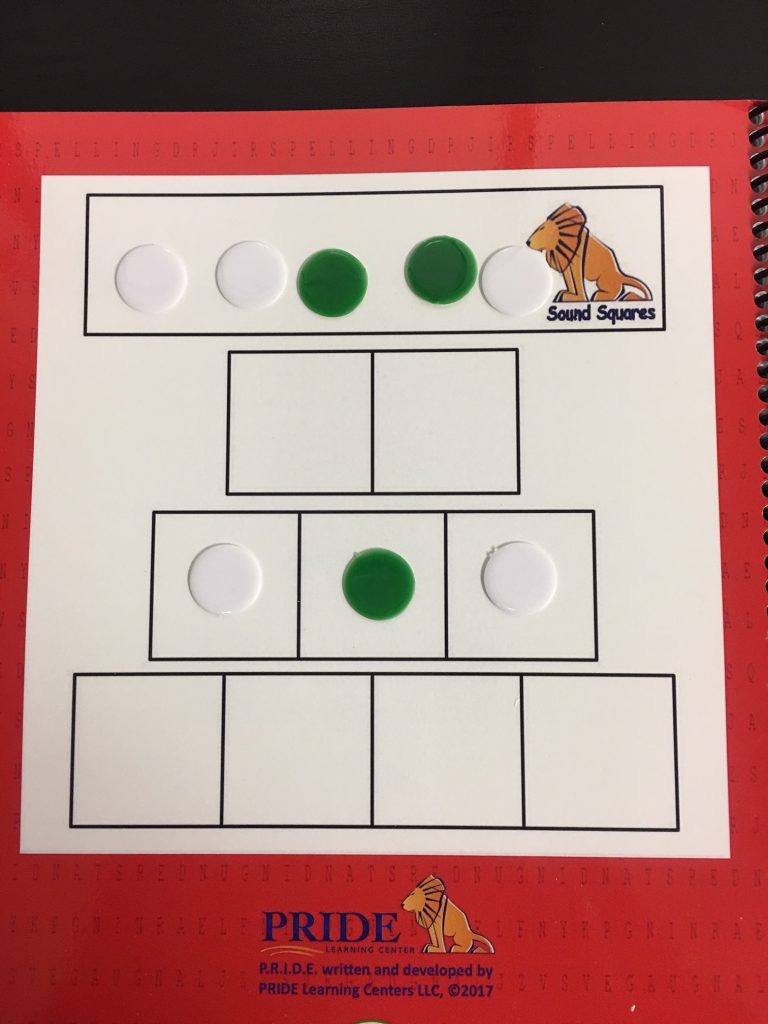

On the back cover of each of the Student’s Workbook there is a set of Elkonin Boxes to help the students build phonemic awareness. The students are instructed to listen to a word and then move the sound tokens into a box for each sound in the word.

As the students progress in the PRIDE program, they eventually break the words apart into syllables, and separate the syllables into sounds.

Success in reading depends on basic phonemic awareness. Without a sense of the sounds that letters represent, the child approaches reading as just memorizing letters. With phonemic awareness, the child can link letters to the sounds in words in order to decipher and spell them. Phonics is an approach to teaching reading in which the child is taught to associate letters with sounds and to use that knowledge to sound words out by blending the sounds from left to right.

It has been well known by researchers for the last 20 years that phonemic awareness and letter knowledge are the two best predictors of how well a child will learn to read during his or her first few years of school. The National Reading Panel’s report confirmed that instruction in phonemic awareness helps children learn early reading skills.

Phonemic Awareness in Action!

Here is a sample video of me teaching a student phonemic awareness with Elkonin Boxes:

Karina Richland, M.A., developed the PRIDE Reading Program, an Orton-Gillingham program for struggling readers, based on her extensive experience working with children with learning differences over the past 30 years. She has been a teacher, educational consultant and the Executive Director of PRIDE Learning Centers in Southern California. For more information, visit the PRIDE Reading Program website here. You can also reach her by email at info@pridelearningcenter.com

by PRIDE Reading Program Admin | Sep 29, 2017 | A PRIDE Post, Dyslexia

This October is National Dyslexia Awareness Month, and PRIDE Learning Centers is helping to spread the word!

Did you know that Dyslexia is estimated to affect some 20-30 percent of our population? This means that more than 2 million school-age children in the United States are dyslexic! We are here to help.

What is Dyslexia?

Although children with dyslexia typically have average to above average intelligence, their dyslexia creates problems not only with reading, writing and spelling but also with speaking, thinking and listening. Often these academic problems can lead to emotional and self-esteem issues throughout their lives. Low self-esteem can lead to poor grades and under achievement. Dyslexic students are often considered lazy, rebellious or unmotivated. These misconceptions cause rejection, isolation, feelings of inferiority, and discouragement.

The central difficulty for dyslexic students is poor phonemic awareness. Phonemic awareness is the ability to appreciate that spoken language is made up of sound segments (phonemes). In other words, a dyslexic student’s brain has trouble breaking a word down into its individual sounds and manipulating these sounds. For example, in a word with three sounds, a dyslexic might only perceive one or two.

Most researchers and teachers agree that developing phonemic awareness is the first step in learning to read. It cannot be skipped. When children begin to learn to read, they first must come to recognize that the word on the page has the same sound structure as the spoken word it represents. However, because dyslexics have difficulty recognizing the internal sound structure of the spoken word to begin with, it is very difficult for them to convert the letters of the alphabet into a phonetic code (decoding).

Although dyslexia can impair spelling and decoding abilities, it also seems to be associated with many strengths and talents. People with dyslexia often have significant strengths in areas controlled by the right side of the brain. These include artistic, athletic and mechanical gifts. Individuals with dyslexia tend to be very bright and creative thinkers. They have a knack for thinking, “outside-the-box.” Many dyslexics have strong 3-D visualization ability, musical talent, creative problem solving skills and intuitive people skills. Many are gifted in math, science, fine arts, journalism, and other creative fields.

Symptoms of Dyslexia

Preschoolers

- Late talking, compared to other children

- Pronunciation problems, reversal of sounds in words (such as ‘aminal’ for ‘animal’ or ‘gabrage’ for ‘garbage’)

- Slow vocabulary growth, often unable to find the right word (takes a while to get the words out)

- Difficulty rhyming words

- Trouble learning numbers, the alphabet, days of the week

- Poor ability to follow directions or routines

- Does not understand what you say until you repeat it a few times

- Enjoys being read to but shows no interest in words or letters

- Has weak fine motor skills (in activities such as drawing, tying laces, cutting, and threading)

- Unstable pencil grip

- Slow to learn new skills, relies heavily on memorization

School Age Children

- Has good memory skills

- Has not shown a dominant handedness

- Seems extremely intelligent but weak in reading

- Reads a word on one page but doesn’t recognize it on the next page or the next day

- Confuses look alike letters like b and d, b and p, n and u, or m and w.

- Substitutes a word while reading that means the same thing but doesn’t look at all similar, like “trip” for “journey” or “mom” for “mother.”

- When reading leaves out or adds small words like “an, a, from, the, to, were, are and of.”

- Reading comprehension is poor because the child spends so much energy trying to figure out words.

- Might have problems tracking the words on the lines, or following them across the pages.

- Avoids reading as much as possible

- Writes illegibly

- Writes everything as one continuous sentence

- Does not understand the difference between a sentence and a fragment of a sentence

- Misspells many words

- Uses odd spacing between words. Might ignore margins completely and pack sentences together on the page instead of spreading them out

- Does not notice spelling errors

- Is easily distracted or has a short attention span

- Is disorganized

- Has difficulties making sense of instructions

- Fails to finish work on time

- Appears lazy, unmotivated, or frustrated

Teenagers

- Avoids reading and writing

- Guesses at words and skips small words

- Has difficulties with reading comprehension

- Does not do homework

- Might say that they are “dumb” or “couldn’t care less”

- Is humiliated

- Might hide the dyslexia by being defiant or using self-abusive behavior

Adults

- Avoids reading and writing

- Types letters in the wrong order

- Has difficulties filling out forms

- Mixes up numbers and dates

- Has low self-esteem

- Might be a high school dropout

- Holds a job below their potential and changes jobs frequently

Treatment

The sooner a child with dyslexia is given proper instruction, particularly in the very early grades, the more likely it is that they will have fewer or milder difficulties later in life.

Older students or adults with dyslexia will need intensive tutoring in reading, writing and spelling using an Orton-Gillingham program. During this training, students will overcome many reading difficulties and learn strategies that will last a lifetime. Treatment will only “stick” if it is incorporated intensively and consistently over time.

Students who have severe dyslexia may need very intensive specialized tutoring to catch up and stay up with the rest of their class. This specialized tutoring helps dyslexic students become successful in reading, writing, spelling, grammar, and vocabulary. It also will help them with math, and word problems. Fortunately, with the proper assistance and help, most students with dyslexia are able to learn to read and develop strategies to become successful readers.

Karina Richland, M.A., developed the PRIDE Reading Program, an Orton-Gillingham program for struggling readers, based on her extensive experience working with children with learning differences over the past 30 years. She has been a teacher, educational consultant and the Executive Director of PRIDE Learning Centers in California. Please feel free to email her with any questions at info@pridelearningcenter.com.

by PRIDE Reading Program Admin | Apr 10, 2017 | Apraxia of Speech, Speech and Reading

Reading is a fundamental skill needed for academic success. In today’s world, strong literacy skills are essential. Children who struggle in reading tend to experience extreme difficulties in all content areas, as every subject in school requires reading proficiency. When children are then faced with further struggles such as Speech Apraxia and receptive and expressive language difficulties, the effects can be even more detrimental.

To read proficiently, a child requires highly integrated skills in word decoding and comprehension and draws upon basic language knowledge such as semantics, syntax, and phonology. Children with speech and language impairments, such as Speech Apraxia, have deficits in phonological processing. For these children, phonemic awareness, motor program execution, syntax and morphology will interfere with the ability to acquire the skills necessary to become proficient readers.

So, how does a child with Speech Apraxia learn how to read?

– With a multisensory, structured, systematic, cumulative and repetitive reading program plus intensive therapy in phonemic awareness and phonological processing!

What is multisensory teaching?

Multisensory teaching is an important aspect of instruction for the child with Speech Apraxia and is used by most clinically trained therapists. Multisensory teaching utilizes all the senses to relay information to the child. The teacher accesses the auditory, visual, and kinesthetic pathways in order to enhance memory and learning. Links are consistently made between the visual (language we see), auditory (language we hear), and kinesthetic-tactile (language we feel) pathways in learning to read. For example, when learning the letter combination “ong” the child might first look at it and then have to trace the letters in the air while speaking out loud. This combination of listening, looking, and moving around creates a lasting impression for the child as things will connect to each other and become memorable.

What is a structured, systematic, cumulative and repetitive reading program?

The other significant component in helping a child with Speech Apraxia learn to read is utilizing an Orton-Gillingham approach. In Orton-Gillingham, the phonemes are introduced in a systematic, sequential and cumulative process. The Orton-Gillingham teacher begins with the most basic elements of the English language. Using repetition and the sequential building blocks of our language, phonemes are taught one at a time. This includes the consonants and sounds of the consonants. By presenting one rule at a time and practicing it until the child can apply it with automaticity and fluency, the child will have no reading gaps in their word-decoding skills. As the child progresses to short vowels, he or she begins reading and writing sounds in isolation. From there the child progresses to digraphs, blends and diphthongs.

Children are taught how to listen to words or syllables and break them into individual phonemes. They also take individual sounds and blend them into a word, change the sounds in the words, delete sounds, and compare sounds. For example, “…in the word bread, what is the first sound you hear? What is the vowel sound you hear? What is the last sound you hear? Students are also taught to recognize and manipulate these sounds. “…what sound does the ‘ea’ make in the word bread? Say bread. Say bread again but instead of the ‘br’ say ‘h.’- HEAD!

Every lesson the child learns is in a structured and orderly fashion. The child is taught a skill and doesn’t progress to the next skill until the current lesson is mastered. As children learn new material, they continue to review old material until it is stored into the child’s long-term memory. While learning these skills, the child focuses on phonemic awareness. There are 181 phonemes or rules in Orton-Gillingham for students to learn. More advanced readers (middle school) will study the rules of English language, syllable patterns, and how to use roots, prefixes, and suffixes to study words. By teaching how to combine the individual letters or sounds and put them together to form words and how to break longer words into smaller pieces, both synthetic and analytic phonics are taught throughout the entire Orton-Gillingham program.

What is phonological processing?

The key to the entire reading process is phonological awareness. This is where a child identifies the different sounds that make words and associates these sounds with written words. A child cannot learn to read without this skill. In order to learn to read, children must be aware of phonemes. A phoneme is the smallest functional unit of sound. For example, the word ‘bench’ contains 4 different phonemes. They are ‘b’ ‘e’ ‘n’ and ‘ch.’

Some examples of phonological awareness tasks include:

- Identifying rhymes – “Tell me all of the words you know that rhyme with the word BAT.”

- Segmenting words into smaller units, such as syllables and sounds, by counting them. “How many sounds do you hear in the word CAKE?”

- Blending separated sounds into words – “What word would we have if we blended these sounds together: /h/ /a/ /t/?”

- Manipulating sounds in words by adding, deleting or substituting – “In the word LAND, change the /L/ to /B/.” “What word is left if you take the /H/ away from the word HAT?”

Through phonological awareness, children learn to associate sounds and create links to word recognition and decoding skills necessary for reading. Research clearly shows that phoneme awareness performance is a strong predictor of long- term reading and spelling success for children with speech and language disabilities. In fact, according to the International Reading Association, phonemic awareness abilities in kindergarten (or in that age range) appear to be the best single predictor of successful reading acquisition!

What kind of reading intervention is necessary?

For the child diagnosed with Speech Apraxia that is already behind his peers in phonemic awareness and reading, the instruction will need to be delivered with great intensity. Keep in mind that this child is behind his classmates and must make more progress if he is to ever catch up. The rest of the class does not stand still to wait, they continue forward. Taking a few lessons once or twice a week will never give the student with Apraxia of Speech the opportunity to catch up. He must make a giant leap; if not, he will always remain behind.

A child with a speech and language disorder may require as much as 150 to 300 hours of intensive instruction if he is ever going to close the reading gap between himself and his peers. The longer identification and effective reading instruction are delayed, the longer the child will need to catch up. In general, it takes 100 hours of intensive instruction to progress one year in reading level. The sooner this remediation is completed, the sooner the child can progress forward with his peers.

Children with Speech Apraxia need more structure, repetition and differentiation in their reading instruction. They need to learn basic language sounds and the letters that make them, starting from the very beginning and moving forward in a gradual step by step process. This needs to be delivered in a systematic, sequential and cumulative approach. For all of this to “stick” the children will need to do this by using their eyes, ears, voices, and hands.

Learn more about the New PRIDE Reading Program

___________________________________________________________________________________________________

Karina Richland, M.A. is the Founder of PRIDE Learning Centers, located in Southern California. Ms. Richland is a certified reading and learning disability specialist. She speaks frequently to parents, teachers, and professionals on learning differences, and writes for several journals and publications. You can visit the PRIDE Learning Center website at: www.pridelearningcenter.com

Page 1 of 712345...»Last »