by PRIDE Reading Program Admin | Aug 30, 2016 | A PRIDE Post, Dyslexia

A parent is asking “Why don’t they test dyslexia in all children?”

My answer is that morally speaking, they should, but legally speaking, all schools are supposed to test children for learning disabilities such as dyslexia when there is a reason to do so. The reason to test dyslexia in a child can be as innocuous as a suspicion on the part of a professional teacher or staff member that something (perhaps) unknown prevents a particular student from learning.

Schools are supposed to act as required by law. There is no absolute requirement to test dyslexia in all children, so schools do not currently assess all students for dyslexia unless there is a particular reason to do so. When a parent, teacher or staff member believes that an assessment may be needed in an area of suspected disability, that belief provides a particular reason to ‘test’ or ‘assess’ whether a learning disability such as dyslexia is present. There are many reasons to believe that a particular child should be assessed for a learning disability.

Imagine being a teacher. You are staring into the faces of 20 eager students seated at their desks and looking at you expectantly. Each one is different. Each one looks different. Each one has a different name. Each one has a different background. Not one of them approach learning in the same way. Some of them have disabilities that impact learning, and all of them have the ability to learn if provided special education services and accommodations.

In my experience in a typical K-12 class, there will be an average of at least five kids in twenty who do not seem to focus on the lessons written on the board or textbooks, who write letters backwards, who seem unable to keep handwritten text organized and spaced properly on a page, who squirm, daydream, speak out of turn, fail to follow directions, become defiant, hate school, and/or distract the class from the lesson plan. Any of these characteristics can be indications that something is preventing each of these students from learning. Students demonstrating any of these behaviors could be candidates for testing dyslexia and assessment if there is a suspicion that a disability may be causing the behaviors interfering with learning.

A disability does not have to actually exist to trigger the law’s duty to ‘Child Find.’ It is enough if there is an area of suspected disability.

Although it is the school’s responsibility to implement ‘Child Find’ policies to identify and then remediate learning disabilities, savvy parents with advocacy experience will always want to assure in advance that everybody does the right thing, and follow-up afterwards. Here’s how we do it: put in writing all reasons for the concerns that a disability may exist. Explain that whatever the cause may be, it is impeding your child’s learning. Cite examples, and ask for a psycho-educational evaluation at the school’s expense to determine whether a learning disability is interfering with your child’s access to the educational curriculum. This will trigger a timeline, and the school will have a certain amount of time to respond. Deadlines do tend to motivate action, but a parent who is pro-active will not wait for the school to schedule an assessment; for many reasons it is advisable to take a child to a private psychologist who specializes in psycho-educational evaluations.

Some parents feel that psychologists employed by a school district have a first loyalty to the school district/employer and not to the child being tested. These parents feel there is a built-in bias or conflict of interest when the testing staff are employees of an entity which may have adverse interests to their child. There are nonprofit organizations and some private psychologists providing sliding fee scales depending on a family’s ability to pay for the private evaluation(s), which can become costly. Finally, the testing psychologist writes a report, or assessment, about a student – these should be written only after careful study, testing, observation, interviews with teachers, staff, parents, friends (if applicable) and review of student’s work product. No single method of evaluation is sufficient to determine whether a learning disability exists.

A parent can call for an individual education plan (IEP) meeting at any time by writing and delivering a letter to the appropriate school staff. Schools may fail in their ‘child find’ efforts, but no parent should! Any parent who believes something is interfering with her child’s ability to read, write, spell, and do math ought to have her child evaluated to see whether a learning disability exists, and find out what can be provided in the way of educational services and accommodations to allow this child to receive an appropriate education.

So, if you think your child has dyslexia, be a squeaky wheel and get a dyslexia test for your child. Nobody will do your child’s educational advocacy for you. For more information, ask someone with experience to teach you to advocate for your child’s educational needs. Be sure to bring every educational document in your possession, including IEP documents, testing from the past, teacher letters, etc.

It is with adult vigilance, follow-through and careful observation that all students who need it will be ‘found’ through ‘Child Find.’ That is, they are identified, assessed, and provided with the educational services and accommodations needed to learn effectively.

Learn more about the New PRIDE Reading Program

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

Nan Waldman, Esq. is a special education and disabilities consultant in Los Angeles with 20 years of experience in the field. She is also a parent and primary caregiver of a child with disabilities, a teacher, an advocate and a lawyer. Nan Waldman, Esq. can be reached by email at n.waldman.esq@gmail.com

by PRIDE Reading Program Admin | Feb 15, 2016 | A PRIDE Post, Learning Disabilities, Reading Comprehension, Reading Skills

Reading is a highly complex, integrated activity that daunts as many as 33 percent of the population. Many children become proficient readers regardless of how they are taught. However, for children who experience difficulty learning to gain meaning from print, reading must be systematically and carefully taught. Mastering the following components of the reading process is essential if students are to become proficient readers.

Appreciation and enthusiasm for reading

It comes as no surprise that children who are passionate about reading are more skillful readers. Reading is more exciting to students when they are:

Read to frequently

Allowed to choose their reading material

Exposed to a wide variety of interesting reading materials

Phonemic awareness

Successful reading depends upon understanding that words are composed of individual sounds. Children need direct teaching in the skills of breaking words into their component sounds and in blending individual sounds together into words. Phonemic awareness is one of the most important skills upon which early reading depends. Children who have poorly developed phonemic awareness skills are at great risk for becoming poor readers.

Phonics and Decoding

Letters of the alphabet are a code representing the sounds in words. Reading involves “decoding” or translating written words into their spoken equivalents. The early stage of decoding instruction emphasizes the correspondence between individual letters or pairs of letters (such as “oa”) and the sounds they represent. Later reading instruction stresses rapid identification of larger units such as syllables. Identifying larger phonetic elements is termed structural analysis. Once a student learns the correspondence between sounds and print, he or she has become a proficient decoder.

Fluent, Automatic Reading of Text

However, in order to become an efficient reader, the decoding process must become fast and accurate. When decoding is efficient, attention and memory processes are available for comprehending what is being read. Reading fluency training is vital for strengthening a student’s comprehension skills. Children should have ample practice reading material that is not difficult for them to decode. This level is referred to as the “independent reading level.” Frequent reading of material at a child’s independent reading level builds automatic word recognition and frees up a child’s mental abilities for comprehension.

Background Knowledge

Comprehension depends heavily on a student’s knowledge of the world. Therefore, the skill of reading comprehension begins to develop long before children enter school. Children who have more experiences of all types, have more background knowledge upon which to base their understanding of written material. Parents help their child develop reading skills when they visit the museum, the park and even the store. Parents and teachers should also read to students in order to help them create a stockpile of information that will facilitate reading comprehension. The best reading instruction teaches a student to access background knowledge while reading.

Vocabulary

Comprehension depends on having a large vocabulary. Children who read widely learn word meanings at a faster rate than children whose reading is more limited either in scope or quantity. During their school years, children should be learning several thousand new words per year. Most of these words are learned by reading.

Written Expression

Reading and writing are two sides of the same coin. Effective reading instruction must include training in expressing one’s thoughts in writing. Children should be given daily practice in organizing and expressing their knowledge through writing. This builds their ability to decode and comprehend the thoughts of other writers.

The key to helping students who experience difficulty in learning to read is to identify a student’s specific reading problems and devise programs which capitalize upon a student’s unique learning strengths. A curriculum that focuses on specific, appropriate, and practical learning strategies will best help students become proficient, efficient and independent readers.

An appropriate literacy goal for all students should be that each is fully able to use reading as a springboard for independent, critical thought and expression. Reading fuels the highest levels of the thinking process. Good readers are armed with tools to become strong thinkers.

Learn more about the New PRIDE Reading Program

________________________________________________________________

Dr. Kari Miller is a board certified educational therapist and director of Miller Educational Excellence, a full-service educational therapy facility in west Los Angeles.

You can visit her website at www.MillerEducationalExcellence.com or email her at klmiller555sbcglobal.net

by PRIDE Reading Program Admin | Jan 31, 2016 | A PRIDE Post, Orton-Gillingham

Learning to read in English would be such a simple task if all similar-sounding phonemes were spelled the same. They aren’t. English is such an unfair language with so many iniquitous rules! For most of us, learning to read means memorizing the symbolic code of letter combinations and then using them in new contexts. Many of us just read naturally, understanding that these letter combinations create words and sounds. Linguists call these sounds ‘phonemes.’ Our brains just register the words and are equipped to read three or four words ahead of time. We are also mentally able to pull words apart, separate them into syllables and apply all of those unfair spelling rules easily and logically.

For a student with a reading disability, this process of reading does NOT come naturally. Students with dyslexia, for example, do not use the process of sounding out phonemes (decoding) while reading and applying spelling rules while writing (encoding). Dyslexics, in general, memorize words in entirety and make mental pictures of each word they learn. The predicament with this strategy is that when they get to a word that they are unfamiliar with, they have no coping mechanisms to attack that particular word.

An example of the difficulty for some of us to learn which combination of letters creates which phoneme is the sound of the letter ‘a’ as in the word ‘cake.’ The long ‘a’ sound is written differently in different words, as in baby, ape, sail, play, steak, vein, eight and they. For students with reading disabilities, something interferes with the acquisition of these written phonemes, and in order to learn, these students must be taught how to read in a different way. One such way is using a multi-sensory method.

Students with a reading disability often struggle with auditory and/or visual processing. They have troubles recalling words and how they are pronounced. This means that they do not comprehend the roles that sounds play in words. These students have difficulties rhyming words as well as blending sounds together to form words. These students do not understand or acquire the alphabetic system expected of them in the early years. If a student with a learning difference is given a task that uses just hearing and vision, without drawing upon other senses, this student will be at a disadvantage. When taught with a multi-sensory approach, students will learn alphabetic patterns, phonemes and words by utilizing all pathways – hearing (auditory), seeing (visual), touching (tactile) and moving (kinesthetic).

When learning the vowel combination ‘oa,’ for example, the student might first look at the letter combination on a picture of a GOAT, then close his/her eyes and listen to the sound, then trace the letters in the air while speaking out loud. This combination of listening, looking, and moving around creates a lasting impression for the student as things will connect to each other and become memorable. Using a multi-sensory approach to reading will benefit ALL learners, not just those with reading disabilities.

The other significant component in helping a struggling reader learn to read and write is utilizing an Orton-Gillingham approach. In Orton-Gillingham, the phonemes are introduced in a systematic, sequential and cumulative process. The Orton-Gillingham teacher begins with the most basic elements of the English language. Using repetition and the sequential building blocks of our language, phonemes are taught one at a time. This includes the consonants and sounds of the consonants. By presenting one rule at a time and practicing it until the student can apply it with automaticity and fluency, students have no reading gaps in their word-decoding skills. As the students progress to short vowels, they begin reading and writing sounds in isolation. From there they progress to digraphs, blends and diphthongs.

Students are taught how to listen to words or syllables and break them into individual phonemes. They also take individual sounds and blend them into a word, change the sounds in the words, delete sounds, and compare sounds. For example, “…in the word steak, what is the first sound you hear? What is the vowel combination you hear? What is the last sound you hear? Students are also taught to recognize and manipulate these sounds. “…what sound does the ‘ea’ make in the word steak? Say steak. Say steak again but instead of the ‘st’ say ‘br.’- BREAK!

Every lesson the student learns is in a structured and orderly fashion. The student is taught a skill and doesn’t progress to the next skill until the current lesson is mastered. As students learn new material, they continue to review old material until it is stored into the student’s long-term memory. While learning these skills, students focus on phonemic awareness. There are 181 phonemes or rules in Orton-Gillingham for students to learn. Advanced students will study the rules of English language, syllable patterns, and how to use roots, prefixes, and suffixes to study words. By teaching how to combine the individual letters or sounds and put them together to form words and how to break longer words into smaller pieces, both synthetic and analytic phonics are taught throughout the entire Orton-Gillingham program.

Students with reading disabilities need more structure, repetition and differentiation in their reading instruction. They need to learn basic language sounds and the letters that make them, starting from the very beginning and moving forward in a gradual step by step process. This needs to be delivered in a systematic, sequential and cumulative approach. For all of this to “stick” the students will need to do this by using their eyes, ears, voices, and hands.

Learn more about the New PRIDE Reading Program

__________________________________________________________________________________

Karina Richland, M.A. is the Managing Director of Pride Learning Centers, located in Southern California. Ms. Richland is a reading and learning disability specialist. She speaks frequently to parents, teachers, and professionals on learning differences, and writes for several journals and publications. You can visit the website www.pridelearningcenter.com

by PRIDE Reading Program Admin | Oct 14, 2015 | A PRIDE Post, Articles & Resources

In the children’s book Madeline, Nurse Clavel is lying in bed when she bolts upright in fright in the middle of the night and says, “Something is not right.”

She had the good sense to trust her intuition about a child in her care. Parents who suspect that something may not be right can trust their intuition and do well to follow Nurse Clavel’s example to get help.

A parent’s intuition is a reliable indicator of the existence of a learning difference or a disability, which interferes with a child’s ability to access the curriculum in school.

When a child is not doing well in school, there may be good reason for you to request an immediate assessment. Responsible parents always want to be certain the school is providing what is needed for their child to succeed in school. To know what is necessary, an assessment is the first thing to do in order to identify the issues to remedy.

What is an assessment?

An assessment is simply a standardized test performed by someone trained and licensed to understand how to give the test and how to interpret the results. The assessor will write a report. If the report indicates a need for special education services or accommodations, school staff and parents in a meeting will discuss the report’s findings.

Parents will receive notice of the meeting. It is called an IEP meeting. An Individual Education Plan designed to provide FAPE, a Free; the IEP team will design Appropriate Public Education. The document, which results from the IEP team meeting, is also called “The IEP.” The IEP is a contract between parents, who are the holders of a child’s educational rights, and the child’s school. There are many ways parents can affect an offer of FAPE, and among them is participating fully in the IEP process, and being certain that all areas of suspected disability are assessed and investigated — thoroughly, fairly and objectively.

How do you get an assessment?

You write a letter to the school and ask for one in a signed and dated letter, describing why you believe your child needs to be assessed.

Be brief, and describe what it is that makes you think an assessment should be performed. If you can, describe the possible disabilities, which prompted your writing: hearing, vision, learning difference, other health impairment, etc.

How is a learning disability remedied?

Students who have been assessed often require more educational services, accommodations, support and/or remediation than those provided to the general student population. These are called ‘special education services’ and Federal and State laws created special education as a civil right.

Are Special Education Services and Accommodations Really Special?

Imagine a pencil taped very high on the wall.

It is not within easy reach for people of average height.

People of average height must jump to reach the pencil and take it off the wall.

People who are very tall will easily extend an arm to reach the pencil and take it down.

People who are very short must stand on a chair to reach the pencil and take it down.

— That chair describes special education services and accommodations.

Here are some insights about our perceptions of those using the chair: The shortest people are no less worthy for needing the chair. The tallest people are no more worthy for not needing the chair. People are people — and some of us need the chair to reach the pencil. The chair levels the playing field.

One in five children have a learning disability, and these range from hardly noticeable to severe. With expert and targeted remedial help — and heaps of extra praise — children with learning disabilities can be taught appropriately and motivated to work extra hard to address their learning needs effectively.

How do you know whether an assessment is needed?

You look for signs and symptoms. A child with a learning disability, for example, will take in and process information differently and needs to be taught by specialists. Some people with learning differences also have another diagnosis, such as ADHD.

Effective early intervention is the key to succeeding in life! It can be a tremendous relief to you as a parent if you understand that success is not necessarily affected by learning differences if learning differences are remedied appropriately – so, the training needed must begin sooner rather than later for the best result. It is heartwarming to see the relief a child feels when their reading ability improves after struggling so long. Their self-esteem improves as their abilities improve.

Because early intervention is best, the sooner parents can identify a learning disability and complete the assessment process, the sooner a child can begin to be taught in a way that makes sense.

What method makes sense?

One that works! Forty percent of children in the United States have difficulties learning to read. Most of these children can learn to read at average grade levels if taught appropriately.

The most well-known and effective method for reading intervention is the Orton-Gillingham approach. With this approach, the teacher presents the building blocks of our language, vowels and consonants, one or two at a time, using a multisensory technique.

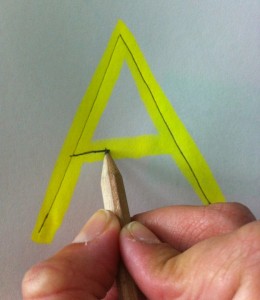

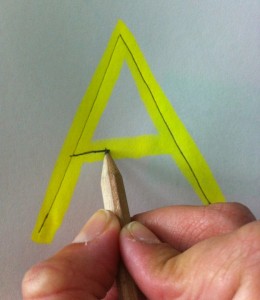

Here is an example of multisensory teaching: prompted by the letter ‘A’ on a flashcard, a student will say it’s name, say its sound, and ‘write’ the letter ‘A’ on their other palm using an inkless index finger. This technique uses sight, hearing, movement and touch.

Orton-Gillingham-trained teachers help students with dyslexia to progress because of the sequential, repetitive and systematic structure of the Orton-Gillingham approach. It is effective, thorough — but also slow. Unfortunately, due to the time requirements in public school classrooms, most teachers cannot incorporate this method into their daily curriculum.

But, you can’t remedy what you don’t thoroughly understand. Here are some indications that an assessment is needed for a learning disability. Other disabilities have other indications for which an assessment can be requested. See www.pridelearningcenter.com for more about learning disabilities.

- Choppy and labored reading

- Reading comprehension inconsistent with intelligence

- Words are omitted or lines of text are skipped over while reading

- Unusual spelling

- Disoriented handwriting

- Easily distracted

- Attention wanders and on-task focus disappears

- Labored writing

- Spatial disorientation

- May ignore margins completely

- May pack words or sentences too tightly on the page

- Disorganized

- Frustrated with expressive written and oral communication

- Doesn’t complete class work or homework on time

- Wrongly accused of being lazy, unmotivated, difficult or unintelligent

- Letter reversals

- Difficulty copying off the board

If, like Nurse Clavel, you find your intuition keeping you awake at night, look for indications that an assessment is needed. And get your child assessed!

About the Authors

Karina Richland, M.A. is the Founder of Pride Learning Centers, located in Los Angeles and Orange County. Ms. Richland is a reading and learning disability specialist. She speaks frequently to parents, teachers, and professionals on learning differences, and writes for several journals and publications. You can reach her by email at karina@pridelearningcenter.com

Learn more about the New PRIDE Reading Program

Nan, Waldman, Esq. is a special education and disabilities consultant in Los Angeles with 20 years of experience in the field. She is also a parent and primary caregiver of a child with disabilities, a teacher, an advocate and a lawyer. Nan Waldman, Esq. can be reached by email at n.waldman.esq@gmail.com

by PRIDE Reading Program Admin | Apr 21, 2015 | A PRIDE Post, Writing Disorder

Dysgraphia is a type of learning disability in which an individual has difficulties putting thoughts to words when writing and the overall writing ability falls substantially below what is normally expected. Children with this sort of difficulty will find any sort of written activity to be a painstaking process and may have great difficulty constructing sentences and paragraphs in a grammatical or logical format and struggle tremendously with note- taking.

Dysgraphia Help – Some common symptoms of dysgraphia are:

- Cramped fingers when grasping pencil or pen

- Unusual pencil grip

- Frequent cross-outs or erasures in written work

- Inconsistent writing, mixture of upper and lower case letters, printed and cursive, variations in letter sizes and irregular formation of letters and slants

- Difficulties writing on the lines or within margins

- Very slow writing

- Easily fatigued while writing

- Illegible handwriting

- Many reversals of letters and numbers

- Some words are written backwards

- Letters might be out of order

- Difficulties organizing thoughts on paper

- Multiple spelling mistakes

- Errors in grammar and punctuation

- Sentences lack cohesion

Here are some examples of how to help a child with Dysgraphia overcome some of their difficulties:

In Preschool or Kindergarten:

- Encourage the correct pencil grip, posture and paper hold while writing. Try to reinforce this often before a habit is formed. Using a rubber band can help keep the correct finger grasp in place.

- Use different pens and pencils that are a comfortable fit for your little one. Sometimes-fat markers on the white board work best for little fingers.

- Use paper with raised lines to help guide staying within the lines.

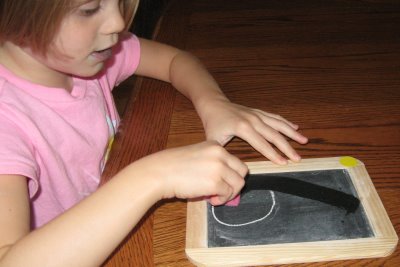

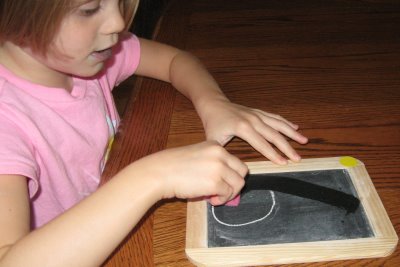

A young child with Dysgraphia will need to practice letter formation using multisensory writing strategies to improve motor memory. They will need to move, touch, feel and manipulate real objects as they learn the habits and skills essential for writing. Some examples are:

1. Have the child first write the letter in the air with two fingers. Then they can trace over a yellow highlighted letter. Finally, they can write the modeled and traced letter independently on a whiteboard or piece of paper.

2. Use the wet-dry-try method. Children write the letter on a chalkboard with a wet sponge using the correct letter formation. Afterwards, they dry the letter with a dry sponge using the correct formation. Then, they rewrite the letter correctly again with a piece of chalk.

3. Build letters out of clay or play dough

4. Use shaving cream to write the letters

5. Trace letters on a piece of sandpaper or a bumpy surface

6. Speak out loud while writing the letters. For example, speaking through motor sequences, such as “b” is “first comes the bat, then comes the ball.”

In Elementary School:

- Introduce a keyboarding program on the computer or tablet as soon as possible. Typing can make it easier for a child with Dysgraphia to write by alleviating the frustration of forming the letters.

- Give the child extra time to complete writing activities.

- Have the child proofread the work later in the day. It is easier to see mistakes after taking a break.

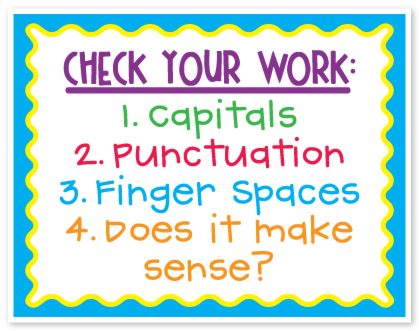

- Help the child create a checklist of editing their own work. This can include spelling, neatness, grammar, syntax, written expression.

- Encourage the use of a spell checker

- Students can first verbally talk into a recorder to express their ideas and then follow up by writing them afterwards.

- Create a well-organized plan that breaks writing assignments into small tasks.

- Use games and movement activities to reinforce spelling and sight words. Some examples are:

- Bounce a Ball – bounce a ball as you spell words. 1 bounce per letter.

- Cheerleader Chant – Give me an S, give me a P, give me an E, give me an L, give me a L, give me another L – what’s that spell? SPELL!

- Jumping Jacks – Instead of writing the words, the student can spell them aloud while doing jumping jacks.

A student with Dysgraphia will benefit from being explicitly taught the steps of the writing process. Just as these students were taught to read in a step-by-step process, they will also need explicit and direct instruction in writing.

Students who struggle with Dysgraphia will need to explicitly be taught different types of writing such as expository and personal essays, short stories, poems, etc. This means that a teacher will need to provide these students with specific ideas and instructions. As part of these writing lessons, students will need to be given “visualization” strategies and mnemonics, which are a fun and easy strategy for remembering essential steps in the writing process.

Children struggling with Dysgraphia will need a structured, sequential, systematic, cumulative and multisensory writing program to help them build lasting memories. This might require more one-on-one sessions with a trained writing teacher, parent or tutor.

Learn more about the New PRIDE Reading Program

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Karina Richland, M.A. is the Founder of PRIDE Learning Centers, located in Los Angeles and Orange County. Ms. Richland is a certified reading and learning disability specialist. Ms. Richland speaks frequently to parents, teachers, and professionals on learning differences, and writes for several journals and publications. You can visit the PRIDE Learning Center website at: www.pridelearningcenter.com