by PRIDE Reading Program Admin | Sep 29, 2017 | A PRIDE Post, Dyslexia

This October is National Dyslexia Awareness Month, and PRIDE Learning Centers is helping to spread the word!

Did you know that Dyslexia is estimated to affect some 20-30 percent of our population? This means that more than 2 million school-age children in the United States are dyslexic! We are here to help.

What is Dyslexia?

Although children with dyslexia typically have average to above average intelligence, their dyslexia creates problems not only with reading, writing and spelling but also with speaking, thinking and listening. Often these academic problems can lead to emotional and self-esteem issues throughout their lives. Low self-esteem can lead to poor grades and under achievement. Dyslexic students are often considered lazy, rebellious or unmotivated. These misconceptions cause rejection, isolation, feelings of inferiority, and discouragement.

The central difficulty for dyslexic students is poor phonemic awareness. Phonemic awareness is the ability to appreciate that spoken language is made up of sound segments (phonemes). In other words, a dyslexic student’s brain has trouble breaking a word down into its individual sounds and manipulating these sounds. For example, in a word with three sounds, a dyslexic might only perceive one or two.

Most researchers and teachers agree that developing phonemic awareness is the first step in learning to read. It cannot be skipped. When children begin to learn to read, they first must come to recognize that the word on the page has the same sound structure as the spoken word it represents. However, because dyslexics have difficulty recognizing the internal sound structure of the spoken word to begin with, it is very difficult for them to convert the letters of the alphabet into a phonetic code (decoding).

Although dyslexia can impair spelling and decoding abilities, it also seems to be associated with many strengths and talents. People with dyslexia often have significant strengths in areas controlled by the right side of the brain. These include artistic, athletic and mechanical gifts. Individuals with dyslexia tend to be very bright and creative thinkers. They have a knack for thinking, “outside-the-box.” Many dyslexics have strong 3-D visualization ability, musical talent, creative problem solving skills and intuitive people skills. Many are gifted in math, science, fine arts, journalism, and other creative fields.

Symptoms of Dyslexia

Preschoolers

- Late talking, compared to other children

- Pronunciation problems, reversal of sounds in words (such as ‘aminal’ for ‘animal’ or ‘gabrage’ for ‘garbage’)

- Slow vocabulary growth, often unable to find the right word (takes a while to get the words out)

- Difficulty rhyming words

- Trouble learning numbers, the alphabet, days of the week

- Poor ability to follow directions or routines

- Does not understand what you say until you repeat it a few times

- Enjoys being read to but shows no interest in words or letters

- Has weak fine motor skills (in activities such as drawing, tying laces, cutting, and threading)

- Unstable pencil grip

- Slow to learn new skills, relies heavily on memorization

School Age Children

- Has good memory skills

- Has not shown a dominant handedness

- Seems extremely intelligent but weak in reading

- Reads a word on one page but doesn’t recognize it on the next page or the next day

- Confuses look alike letters like b and d, b and p, n and u, or m and w.

- Substitutes a word while reading that means the same thing but doesn’t look at all similar, like “trip” for “journey” or “mom” for “mother.”

- When reading leaves out or adds small words like “an, a, from, the, to, were, are and of.”

- Reading comprehension is poor because the child spends so much energy trying to figure out words.

- Might have problems tracking the words on the lines, or following them across the pages.

- Avoids reading as much as possible

- Writes illegibly

- Writes everything as one continuous sentence

- Does not understand the difference between a sentence and a fragment of a sentence

- Misspells many words

- Uses odd spacing between words. Might ignore margins completely and pack sentences together on the page instead of spreading them out

- Does not notice spelling errors

- Is easily distracted or has a short attention span

- Is disorganized

- Has difficulties making sense of instructions

- Fails to finish work on time

- Appears lazy, unmotivated, or frustrated

Teenagers

- Avoids reading and writing

- Guesses at words and skips small words

- Has difficulties with reading comprehension

- Does not do homework

- Might say that they are “dumb” or “couldn’t care less”

- Is humiliated

- Might hide the dyslexia by being defiant or using self-abusive behavior

Adults

- Avoids reading and writing

- Types letters in the wrong order

- Has difficulties filling out forms

- Mixes up numbers and dates

- Has low self-esteem

- Might be a high school dropout

- Holds a job below their potential and changes jobs frequently

Treatment

The sooner a child with dyslexia is given proper instruction, particularly in the very early grades, the more likely it is that they will have fewer or milder difficulties later in life.

Older students or adults with dyslexia will need intensive tutoring in reading, writing and spelling using an Orton-Gillingham program. During this training, students will overcome many reading difficulties and learn strategies that will last a lifetime. Treatment will only “stick” if it is incorporated intensively and consistently over time.

Students who have severe dyslexia may need very intensive specialized tutoring to catch up and stay up with the rest of their class. This specialized tutoring helps dyslexic students become successful in reading, writing, spelling, grammar, and vocabulary. It also will help them with math, and word problems. Fortunately, with the proper assistance and help, most students with dyslexia are able to learn to read and develop strategies to become successful readers.

Karina Richland, M.A., developed the PRIDE Reading Program, an Orton-Gillingham program for struggling readers, based on her extensive experience working with children with learning differences over the past 30 years. She has been a teacher, educational consultant and the Executive Director of PRIDE Learning Centers in California. Please feel free to email her with any questions at info@pridelearningcenter.com.

by PRIDE Reading Program Admin | Aug 29, 2017 | A PRIDE Post, Apraxia of Speech

Apraxia of Speech is a speech disorder that makes it difficult for children to correctly pronounce syllables and words. When a child struggles with saying the sounds, they simultaneously struggle with reading, writing and comprehending the sounds.

To read proficiently, a child requires highly integrated skills in word decoding and comprehension and draws upon basic language knowledge such as semantics, syntax, and phonology. Children with speech and language impairments, such as Childhood Apraxia of Speech (CAS), have deficits in phonological processing. For these children, phonemic awareness, motor program execution, syntax and morphology will interfere with the ability to acquire the skills necessary to become proficient readers.

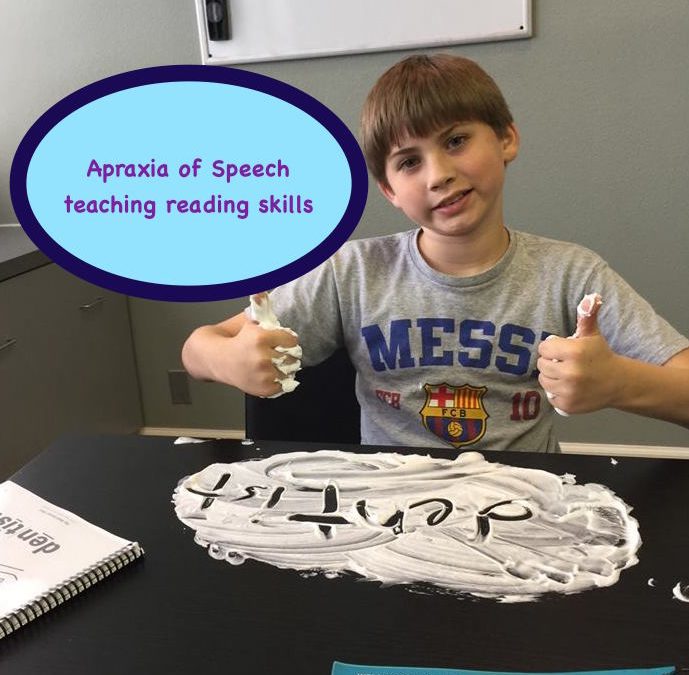

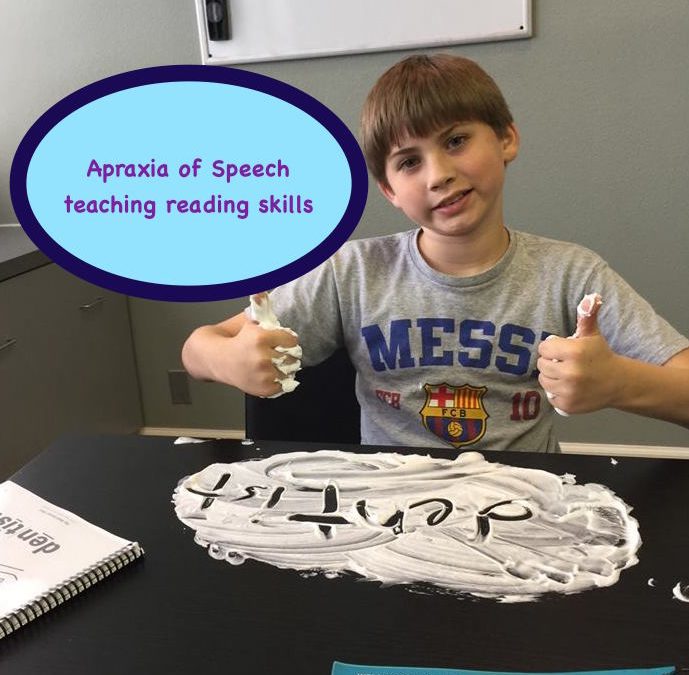

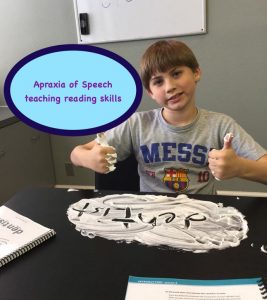

So… how does a child with Apraxia of Speech learn how to read?

With a multisensory, structured, systematic, cumulative and repetitive reading program plus intensive therapy in phonemic awareness and phonological processing!

What does multi-sensory mean?

See it – Say it – Move with it – Touch it!

Multisensory teaching is an important aspect of instruction for the child with Apraxia of Speech and is used by most clinically trained therapists. Multisensory teaching utilizes all the senses to relay information to the child. The teacher accesses the auditory, visual, and kinesthetic pathways in order to enhance memory and learning. Links are consistently made between the visual (language we see), auditory (language we hear), and kinesthetic-tactile (language we feel) pathways in learning to read. For example, when learning the letter combination “ong” the child might first look at it and then have to trace the letters in the air while speaking out loud. This combination of listening, looking, and moving around creates a lasting impression for the child as things will connect to each other and become memorable.

What is a structured, systematic, cumulative and repetitive reading program?

The Orton-Gillingham approach is the best!

The most significant component in helping a child with Apraxia of Speech learn to read is utilizing an Orton-Gillingham approach. In Orton-Gillingham, the phonemes are introduced in a systematic, sequential and cumulative process. The Orton-Gillingham teacher begins with the most basic elements of the English language. Using repetition and the sequential building blocks of our language, phonemes are taught one at a time. This includes the consonants and sounds of the consonants. By presenting one rule at a time and practicing it until the child can apply it with automaticity and fluency, the child will have no reading gaps in their word-decoding skills. As the child progresses to short vowels, he or she begins reading and writing sounds in isolation. From there the child progresses to digraphs, blends and diphthongs.

Children are taught how to listen to words or syllables and break them into individual phonemes. They also take individual sounds and blend them into a word, change the sounds in the words, delete sounds, and compare sounds. For example, “…in the word bread, what is the first sound you hear? What is the vowel sound you hear? What is the last sound you hear? Students are also taught to recognize and manipulate these sounds. “…what sound does the ‘ea’ make in the word bread? Say bread. Say bread again but instead of the ‘br’ say ‘h.’- HEAD!

Every lesson the child learns is in a structured and orderly fashion. The child is taught a skill and doesn’t progress to the next skill until the current lesson is mastered. As children learn new material, they continue to review old material until it is stored into the child’s long-term memory. While learning these skills, the child focuses on phonemic awareness. There are 181 phonemes or rules in Orton-Gillingham for students to learn. More advanced readers (middle school) will study the rules of English language, syllable patterns, and how to use roots, prefixes, and suffixes to study words. By teaching how to combine the individual letters or sounds and put them together to form words and how to break longer words into smaller pieces, both synthetic and analytic phonics are taught throughout the entire Orton-Gillingham program.

What is Phonological Processing?

The key to the entire reading process is phonological awareness. This is where a child identifies the different sounds that make words and associates these sounds with written words. A child cannot learn to read without this skill. In order to learn to read, children must be aware and able to sound out each of the phonemes in the English language. A phoneme is the smallest functional unit of sound. For example, the word ‘bench’ contains 4 different phonemes. They are ‘b’ ‘e’ ‘n’ and ‘ch.’

What are some activities in phonological awareness that help?

- Identifying rhymes – “Tell me all of the words you know that rhyme with the word BAT.”

- Segmenting words into smaller units, such as syllables and sounds, by counting them. “How many sounds do you hear in the word CAKE?”

- Blending separated sounds into words – “What word would we have if we blended these sounds together: /h/ /a/ /t/?”

- Manipulating sounds in words by adding, deleting or substituting – “In the word LAND, change the /L/ to /B/.” “What word is left if you take the /H/ away from the word HAT?”

Through phonological awareness, children learn to associate sounds and create links to word recognition and decoding skills necessary for reading. Research clearly shows that phoneme awareness performance is a strong predictor of long- term reading and spelling success for children with speech and language disabilities. In fact, according to the International Reading Association, phonemic awareness abilities in kindergarten (or in that age range) appear to be the best single predictor of successful reading acquisition!

What kind of reading intervention is necessary?

For the child diagnosed with Apraxia of Speech that is already behind his peers in phonemic awareness and reading, the instruction will need to be delivered with great intensity. Keep in mind that this child is behind his classmates and must make more progress if he is to ever catch up. The rest of the class does not stand still to wait, they continue forward. Taking a few lessons once or twice a week will never give the student with CAS the opportunity to catch up. He must make a giant leap; if not, he will always remain behind.

An older child with a speech and language disorder may require as much as 150 to 300 hours of intensive instruction if he or she is ever going to close the reading gap between himself and his peers. The longer identification and effective reading instruction are delayed, the longer the child will need to catch up. In general, it takes 100 hours of intensive instruction to progress one year in reading level. The sooner this remediation is completed, the sooner the child can progress forward with his or her peers.

Children with Apraxia of Speech need more structure, repetition and differentiation in their reading instruction. They need to learn basic language sounds and the letters that make them, starting from the very beginning and moving forward in a gradual step by step process. This needs to be delivered in a systematic, sequential and cumulative approach. For all of this to “stick” the children will need to do this by using their eyes, ears, voices, and hands.

Where do I find an Orton-Gillingham Reading Curriculum?

Click on the video below

If you enjoyed reading this Blog Post, you might also enjoy reading Apraxia of Speech Reading Books. Thank you so much for visiting my blog today!

Karina Richland, M.A., developed the PRIDE Reading Program, an Orton-Gillingham program for struggling readers, based on her extensive experience working with children with learning differences over the past 30 years. She has been a teacher, educational consultant and the Executive Director of PRIDE Learning Centers in Southern California. Please feel free to email her with any questions at info@pridelearningcenter.com. Visit the PRIDE Reading Program website at https://www.pridereadingprogram.com

by PRIDE Reading Program Admin | Jul 12, 2017 | A PRIDE Post, Auditory Processing Disorder

The ability to process and learn from oral instructions and oral information is a fundamental skill required throughout life. So how can you help your child strengthen these skills? Here is a list of very easy do it at home activities that you can practice throughout the day to strengthen your child’s auditory processing.

End of the day review

Every night as you tuck your child into bed, discuss the events of the day. Have your child try to remember all the wonderful (or not so wonderful) things that happened that day. Can your child recall the events sequentially?

Play the game – what’s next?

Pick a room in your house and give your child two instructions. For example, “go into the dining room, grab a spoon and hide under the table.” Try to build up to 3 instructions over time. Then switch so that your child gets to give you instructions to follow too.

Follow my rhythm

You can clap a short pattern and have your child repeat it. Make it simple at first (one slow clap, two fast ones and then a slow one). Then slowly increase the complexity and loudness of the claps. Then ask your child to make up a pattern for you to repeat.

I went to the market and I bought…

This is a family game and can be played around the dinner table. Start with “I went to the market and I bought an apple.” The second person says, “I went to the market and I bought an apple an a banana.” The third person says, “I went to the market and I bought an apple and a banana and a bag of chips.” Etc. etc…

Listen to music and memorize the lyrics

Have your child listen to a song and learn to sing the lyrics. Give your child a song that they are unfamiliar with or one that they do not know the words to already. Replay the tune often until your child can sing the entire song.

Listen to Audio books

Audio books force a child to listen. Pick a story that your child enjoys and is excited about listening to. Don’t hesitate to choose books they have already read. Repetition builds understanding, and we all love to read or listen to our favorite books over and over again.

Play Mother May I

Have your child line up and face you (about 20 feet away). Then give your child 2 commands such as, “Take 3 steps forward and touch your nose with your right pinky finger. Or, hop forward 2 hops then do the chicken dance.” The child will ask, “Mother may I?” You answer yes or no. When your child finally gets to you – switch roles. Eventually try to get up to 3 commands.

Memorize a Poem

Have your child memorize a poem and recite it to you. Aim for memorization of at least four to eight short poems during the school year. Keep reciting the old ones and build up a repertoire. Try to pick poems that the child has read and enjoyed. This can begin with simple fun ones and then eventually increase to some rich and deep poetry too.

When you strengthen your child’s auditory processing skills, remember to make it a fun experience for both you and them. Just a few minutes a day with some of the above mentioned activities will hopefully make a big difference.

Learn more about the New PRIDE Reading Program

________________________________________________________________________________

Karina Richland, M.A., developed the PRIDE Reading Program, an Orton-Gillingham program for struggling readers, based on her extensive experience working with children with learning differences over the past 30 years. She has been a teacher, educational consultant and the Executive Director of PRIDE Learning Centers in Southern California. Please feel free to email her with any questions at info@pridelearningcenter.com.

by PRIDE Reading Program Admin | Apr 15, 2017 | A PRIDE Post, Reading Disability

Although children do develop at different rates, attributing a struggling reader to immaturity is risky and usually unhelpful. Children, who are poor readers at the end of first grade, are most often still poor readers in fourth grade.

Early signs of reading problems should never be ignored or passed off as a developmental lag. It is never a good idea to “wait and see” if a child grows out it. The safest assumption is that early, direct teaching designed to help a struggling reader will minimize risks later on. If a child is taught the sounds, letters, words, and language comprehension skills necessary by the end of first grade, most of these children will avoid failure.

Reading intervention in kindergarten and first grade is more effective than intervention in fourth grade and older. This is because early intervention takes less time and resources to close the reading gap than using remediation strategies in reading later on. According to The National Institute of Child Health and Human Department, 90% of poor readers can increase reading skills to average reading levels with prevention and early intervention programs that combine instruction in phonemic awareness, phonics, spelling, reading fluency, and reading comprehension provided by highly qualified and well-trained teachers. It takes four times as long to improve the skills of a struggling reader in fourth grade as it does to do so between mid-kindergarten and first grade. In other words, it takes two hours a day in fourth grade to have the same impact as thirty minutes a day in first grade. If intervention is not provided until nine years of age, approximately 75 to 88 % of these children will continue to have reading difficulties throughout high school and their adult lives.

Although there is a crucial window of opportunity (kindergarten to middle of first grade) parents need to know that it is never too late to help a struggling reader. Older children can be taught to read but the instruction may be harder to arrange, it will take more time, and it will require an intensive effort from the teacher, the student, and the parent.

On the whole, delayed intervention is costlier to everyone, including the child. These children will be more likely to develop confidence, enjoy reading, read more, and read better if they get off to the right start.

Karina Richland, M.A., is the Founder of PRIDE Learning Centers, located in Southern California. Ms. Richland is a certified reading and learning disability specialist and speaks frequently to parents, teachers, and professionals on learning differences. She is also the author of the PRIDE Reading Program, an Orton-Gillingham approach to teaching reading, writing and comprehension. You can visit the PRIDE Learning Center website at: www.pridelearningcenter.com

by PRIDE Reading Program Admin | Apr 10, 2017 | Apraxia of Speech, Speech and Reading

Reading is a fundamental skill needed for academic success. In today’s world, strong literacy skills are essential. Children who struggle in reading tend to experience extreme difficulties in all content areas, as every subject in school requires reading proficiency. When children are then faced with further struggles such as Speech Apraxia and receptive and expressive language difficulties, the effects can be even more detrimental.

To read proficiently, a child requires highly integrated skills in word decoding and comprehension and draws upon basic language knowledge such as semantics, syntax, and phonology. Children with speech and language impairments, such as Speech Apraxia, have deficits in phonological processing. For these children, phonemic awareness, motor program execution, syntax and morphology will interfere with the ability to acquire the skills necessary to become proficient readers.

So, how does a child with Speech Apraxia learn how to read?

– With a multisensory, structured, systematic, cumulative and repetitive reading program plus intensive therapy in phonemic awareness and phonological processing!

What is multisensory teaching?

Multisensory teaching is an important aspect of instruction for the child with Speech Apraxia and is used by most clinically trained therapists. Multisensory teaching utilizes all the senses to relay information to the child. The teacher accesses the auditory, visual, and kinesthetic pathways in order to enhance memory and learning. Links are consistently made between the visual (language we see), auditory (language we hear), and kinesthetic-tactile (language we feel) pathways in learning to read. For example, when learning the letter combination “ong” the child might first look at it and then have to trace the letters in the air while speaking out loud. This combination of listening, looking, and moving around creates a lasting impression for the child as things will connect to each other and become memorable.

What is a structured, systematic, cumulative and repetitive reading program?

The other significant component in helping a child with Speech Apraxia learn to read is utilizing an Orton-Gillingham approach. In Orton-Gillingham, the phonemes are introduced in a systematic, sequential and cumulative process. The Orton-Gillingham teacher begins with the most basic elements of the English language. Using repetition and the sequential building blocks of our language, phonemes are taught one at a time. This includes the consonants and sounds of the consonants. By presenting one rule at a time and practicing it until the child can apply it with automaticity and fluency, the child will have no reading gaps in their word-decoding skills. As the child progresses to short vowels, he or she begins reading and writing sounds in isolation. From there the child progresses to digraphs, blends and diphthongs.

Children are taught how to listen to words or syllables and break them into individual phonemes. They also take individual sounds and blend them into a word, change the sounds in the words, delete sounds, and compare sounds. For example, “…in the word bread, what is the first sound you hear? What is the vowel sound you hear? What is the last sound you hear? Students are also taught to recognize and manipulate these sounds. “…what sound does the ‘ea’ make in the word bread? Say bread. Say bread again but instead of the ‘br’ say ‘h.’- HEAD!

Every lesson the child learns is in a structured and orderly fashion. The child is taught a skill and doesn’t progress to the next skill until the current lesson is mastered. As children learn new material, they continue to review old material until it is stored into the child’s long-term memory. While learning these skills, the child focuses on phonemic awareness. There are 181 phonemes or rules in Orton-Gillingham for students to learn. More advanced readers (middle school) will study the rules of English language, syllable patterns, and how to use roots, prefixes, and suffixes to study words. By teaching how to combine the individual letters or sounds and put them together to form words and how to break longer words into smaller pieces, both synthetic and analytic phonics are taught throughout the entire Orton-Gillingham program.

What is phonological processing?

The key to the entire reading process is phonological awareness. This is where a child identifies the different sounds that make words and associates these sounds with written words. A child cannot learn to read without this skill. In order to learn to read, children must be aware of phonemes. A phoneme is the smallest functional unit of sound. For example, the word ‘bench’ contains 4 different phonemes. They are ‘b’ ‘e’ ‘n’ and ‘ch.’

Some examples of phonological awareness tasks include:

- Identifying rhymes – “Tell me all of the words you know that rhyme with the word BAT.”

- Segmenting words into smaller units, such as syllables and sounds, by counting them. “How many sounds do you hear in the word CAKE?”

- Blending separated sounds into words – “What word would we have if we blended these sounds together: /h/ /a/ /t/?”

- Manipulating sounds in words by adding, deleting or substituting – “In the word LAND, change the /L/ to /B/.” “What word is left if you take the /H/ away from the word HAT?”

Through phonological awareness, children learn to associate sounds and create links to word recognition and decoding skills necessary for reading. Research clearly shows that phoneme awareness performance is a strong predictor of long- term reading and spelling success for children with speech and language disabilities. In fact, according to the International Reading Association, phonemic awareness abilities in kindergarten (or in that age range) appear to be the best single predictor of successful reading acquisition!

What kind of reading intervention is necessary?

For the child diagnosed with Speech Apraxia that is already behind his peers in phonemic awareness and reading, the instruction will need to be delivered with great intensity. Keep in mind that this child is behind his classmates and must make more progress if he is to ever catch up. The rest of the class does not stand still to wait, they continue forward. Taking a few lessons once or twice a week will never give the student with Apraxia of Speech the opportunity to catch up. He must make a giant leap; if not, he will always remain behind.

A child with a speech and language disorder may require as much as 150 to 300 hours of intensive instruction if he is ever going to close the reading gap between himself and his peers. The longer identification and effective reading instruction are delayed, the longer the child will need to catch up. In general, it takes 100 hours of intensive instruction to progress one year in reading level. The sooner this remediation is completed, the sooner the child can progress forward with his peers.

Children with Speech Apraxia need more structure, repetition and differentiation in their reading instruction. They need to learn basic language sounds and the letters that make them, starting from the very beginning and moving forward in a gradual step by step process. This needs to be delivered in a systematic, sequential and cumulative approach. For all of this to “stick” the children will need to do this by using their eyes, ears, voices, and hands.

Learn more about the New PRIDE Reading Program

___________________________________________________________________________________________________

Karina Richland, M.A. is the Founder of PRIDE Learning Centers, located in Southern California. Ms. Richland is a certified reading and learning disability specialist. She speaks frequently to parents, teachers, and professionals on learning differences, and writes for several journals and publications. You can visit the PRIDE Learning Center website at: www.pridelearningcenter.com

Page 3 of 18«12345...10...»Last »