by PRIDE Reading Program Admin | Aug 29, 2017 | A PRIDE Post, Apraxia of Speech

Apraxia of Speech is a speech disorder that makes it difficult for children to correctly pronounce syllables and words. When a child struggles with saying the sounds, they simultaneously struggle with reading, writing and comprehending the sounds.

To read proficiently, a child requires highly integrated skills in word decoding and comprehension and draws upon basic language knowledge such as semantics, syntax, and phonology. Children with speech and language impairments, such as Childhood Apraxia of Speech (CAS), have deficits in phonological processing. For these children, phonemic awareness, motor program execution, syntax and morphology will interfere with the ability to acquire the skills necessary to become proficient readers.

So… how does a child with Apraxia of Speech learn how to read?

With a multisensory, structured, systematic, cumulative and repetitive reading program plus intensive therapy in phonemic awareness and phonological processing!

What does multi-sensory mean?

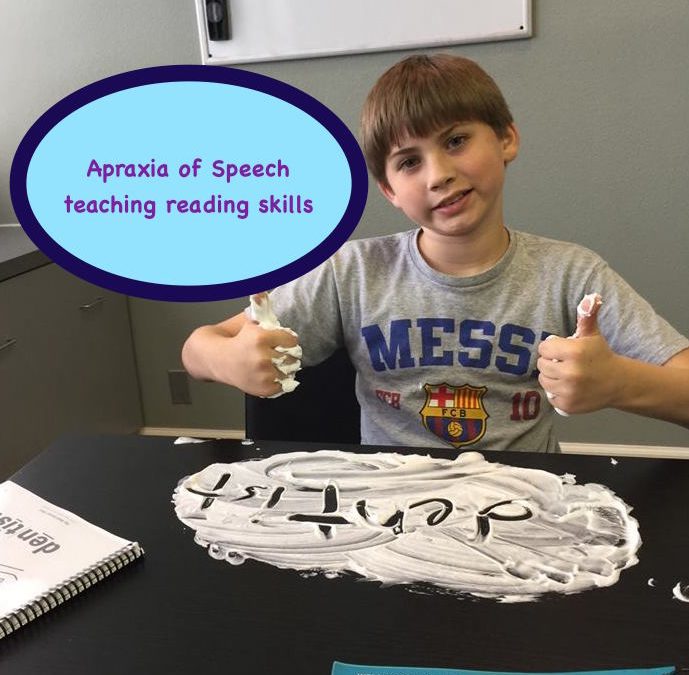

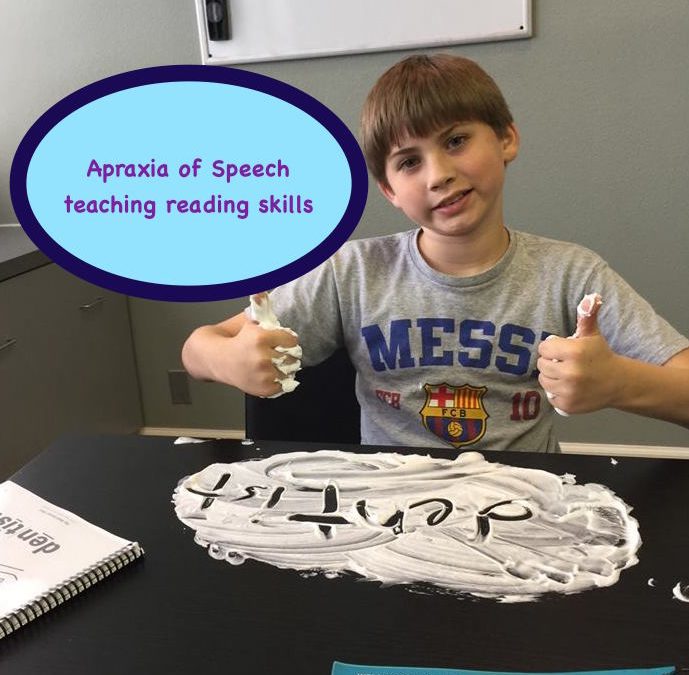

See it – Say it – Move with it – Touch it!

Multisensory teaching is an important aspect of instruction for the child with Apraxia of Speech and is used by most clinically trained therapists. Multisensory teaching utilizes all the senses to relay information to the child. The teacher accesses the auditory, visual, and kinesthetic pathways in order to enhance memory and learning. Links are consistently made between the visual (language we see), auditory (language we hear), and kinesthetic-tactile (language we feel) pathways in learning to read. For example, when learning the letter combination “ong” the child might first look at it and then have to trace the letters in the air while speaking out loud. This combination of listening, looking, and moving around creates a lasting impression for the child as things will connect to each other and become memorable.

What is a structured, systematic, cumulative and repetitive reading program?

The Orton-Gillingham approach is the best!

The most significant component in helping a child with Apraxia of Speech learn to read is utilizing an Orton-Gillingham approach. In Orton-Gillingham, the phonemes are introduced in a systematic, sequential and cumulative process. The Orton-Gillingham teacher begins with the most basic elements of the English language. Using repetition and the sequential building blocks of our language, phonemes are taught one at a time. This includes the consonants and sounds of the consonants. By presenting one rule at a time and practicing it until the child can apply it with automaticity and fluency, the child will have no reading gaps in their word-decoding skills. As the child progresses to short vowels, he or she begins reading and writing sounds in isolation. From there the child progresses to digraphs, blends and diphthongs.

Children are taught how to listen to words or syllables and break them into individual phonemes. They also take individual sounds and blend them into a word, change the sounds in the words, delete sounds, and compare sounds. For example, “…in the word bread, what is the first sound you hear? What is the vowel sound you hear? What is the last sound you hear? Students are also taught to recognize and manipulate these sounds. “…what sound does the ‘ea’ make in the word bread? Say bread. Say bread again but instead of the ‘br’ say ‘h.’- HEAD!

Every lesson the child learns is in a structured and orderly fashion. The child is taught a skill and doesn’t progress to the next skill until the current lesson is mastered. As children learn new material, they continue to review old material until it is stored into the child’s long-term memory. While learning these skills, the child focuses on phonemic awareness. There are 181 phonemes or rules in Orton-Gillingham for students to learn. More advanced readers (middle school) will study the rules of English language, syllable patterns, and how to use roots, prefixes, and suffixes to study words. By teaching how to combine the individual letters or sounds and put them together to form words and how to break longer words into smaller pieces, both synthetic and analytic phonics are taught throughout the entire Orton-Gillingham program.

What is Phonological Processing?

The key to the entire reading process is phonological awareness. This is where a child identifies the different sounds that make words and associates these sounds with written words. A child cannot learn to read without this skill. In order to learn to read, children must be aware and able to sound out each of the phonemes in the English language. A phoneme is the smallest functional unit of sound. For example, the word ‘bench’ contains 4 different phonemes. They are ‘b’ ‘e’ ‘n’ and ‘ch.’

What are some activities in phonological awareness that help?

- Identifying rhymes – “Tell me all of the words you know that rhyme with the word BAT.”

- Segmenting words into smaller units, such as syllables and sounds, by counting them. “How many sounds do you hear in the word CAKE?”

- Blending separated sounds into words – “What word would we have if we blended these sounds together: /h/ /a/ /t/?”

- Manipulating sounds in words by adding, deleting or substituting – “In the word LAND, change the /L/ to /B/.” “What word is left if you take the /H/ away from the word HAT?”

Through phonological awareness, children learn to associate sounds and create links to word recognition and decoding skills necessary for reading. Research clearly shows that phoneme awareness performance is a strong predictor of long- term reading and spelling success for children with speech and language disabilities. In fact, according to the International Reading Association, phonemic awareness abilities in kindergarten (or in that age range) appear to be the best single predictor of successful reading acquisition!

What kind of reading intervention is necessary?

For the child diagnosed with Apraxia of Speech that is already behind his peers in phonemic awareness and reading, the instruction will need to be delivered with great intensity. Keep in mind that this child is behind his classmates and must make more progress if he is to ever catch up. The rest of the class does not stand still to wait, they continue forward. Taking a few lessons once or twice a week will never give the student with CAS the opportunity to catch up. He must make a giant leap; if not, he will always remain behind.

An older child with a speech and language disorder may require as much as 150 to 300 hours of intensive instruction if he or she is ever going to close the reading gap between himself and his peers. The longer identification and effective reading instruction are delayed, the longer the child will need to catch up. In general, it takes 100 hours of intensive instruction to progress one year in reading level. The sooner this remediation is completed, the sooner the child can progress forward with his or her peers.

Children with Apraxia of Speech need more structure, repetition and differentiation in their reading instruction. They need to learn basic language sounds and the letters that make them, starting from the very beginning and moving forward in a gradual step by step process. This needs to be delivered in a systematic, sequential and cumulative approach. For all of this to “stick” the children will need to do this by using their eyes, ears, voices, and hands.

Where do I find an Orton-Gillingham Reading Curriculum?

Click on the video below

If you enjoyed reading this Blog Post, you might also enjoy reading Apraxia of Speech Reading Books. Thank you so much for visiting my blog today!

Karina Richland, M.A., developed the PRIDE Reading Program, an Orton-Gillingham program for struggling readers, based on her extensive experience working with children with learning differences over the past 30 years. She has been a teacher, educational consultant and the Executive Director of PRIDE Learning Centers in Southern California. Please feel free to email her with any questions at info@pridelearningcenter.com. Visit the PRIDE Reading Program website at https://www.pridereadingprogram.com

by PRIDE Reading Program Admin | Oct 16, 2016 | A PRIDE Post, ADHD, Dyslexia

The diagnosis of dyslexia is often missed by child psychiatrists, who are frequently asked to validate a diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), generated from a psychological evaluation because ADHD is a fairly common disorder with a prevalence of 10% in the US, and because roughly 80% of children with ADHD respond to stimulant medication, the role of a child psychiatrist is often circumscribed to diagnosing and treating ADHD with medication. However, because the dyslexia/ADHD co-morbidity, i.e., “the parallel track diagnosis” of ADHD and dyslexia has been described to be in the range of 10% (Shaywitz, 1988), child psychiatrists often confuse the 20% population of children and adolescents who epidemiologically are not expected to respond to stimulant medications with children with disorders of dyslexia/ADHD comorbidity.

Bruce Pennington (1991) an established authority in the field of dyslexia has suggested that there is no robust two-way association between dyslexia and ADHD, i.e., that increased prevalence of dyslexia in children with ADHD is lacking in several studies, whereas there are increased rates of ADHD in dyslexic samples described. To translate this into a more comprehensive language, I quote my former teacher at UCLA the late Dr. Dennis Cantwell who said:

“When you hear horse hooves around the corner you should suspect the zebra, because if you don’t – you may miss the unicorn.”

Whenever I evaluate a child who has been referred for assessment of probable ADHD, I also include a screening instrument for dyslexia as part of the evaluation. Conversely, if a child who has been properly diagnosed with dyslexia is referred to me for further assessment, I assume that she/he may also have dyslexia/ADHD comorbidity. It is important to remember that although the diagnostic statistical manual (DSM) has trained us all into the habit of diagnosing by categories; many of these disorders are not necessarily categorical, instead present on a dimensional range. That is to say that a child may have mild, moderate or severe dyslexia, as well as the equivalent degrees of ADHD severity. A few additional points deserve to be emphasized on dyslexia and ADHD comorbidity:

1. If a child is diagnosed with dyslexia, there are no medication treatments proven to be efficacious. The treatment of dyslexia is complex. According to authors like Pennington and others it involves a phonic-based approach to reading because the problem of phonological coding is so central to the disorder. Examples of programs, which teach letter sound relations, are the Orton Gillingham, DISTAR, etc. The issue of remediation of spelling dyslexia seems to be fairly complex and several centers do not make spelling a direct target of remediation.

2. Authors like Pennington have advised against the idea of parents tutoring their dyslexic children, not just because they lack specific expertise but because there is a conflict between the two roles that make a parent-child tutoring situation too emotionally charged to be successful.

3. I believe a psychiatrist should treat whatever degree of inattention secondary to ADHD may exist on a child with dyslexia. While minimizing any potential side effects from stimulant medication, i.e. loss of appetite and weight, it is worthwhile optimizing inattention deficits through the prescription of medication on a child with dyslexia.

4. There are diagnostic boundaries that need to be monitored on a longitudinal basis. In other words, if the expectation of parents or teachers is that with remediation of inattention through medication management, deficiencies secondary to dyslexia will also fall into place, these assumptions have to be identified and corrected. This is often a set up for delaying the necessary treatment of a child with dyslexia. This delay is often painful to witness because the large majority of children with untreated dyslexia eventually become demoralized, some of them clinically depressed. I have seen in 15 years of practice, children with dyslexia who barely compensate for their deficiencies in an educational environment that is still very alphabetic so to speak, for example in the teaching of languages, (heavily relying on grammar). As time goes by, children with untreated dyslexia become school avoidant, and often resort to maladaptive patterns in order to compensate for loss of self-esteem.

For more information regarding dyslexia/ADHD morbidity or to have your child evaluated for a screening please feel free to contact Dr. Pablo De Amesti Davanzo below.

Learn more about the New PRIDE Reading Program

________________________________________________________________________________________________

Dr. Pablo De Amesti Davanzo, MD is Senate Emeritus of Psychiatry, University of California, Los Angeles and former National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Career Development Awardee. He completed his residency training in Psychiatry at Duke University in 1993 and his fellowship training in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at UCLA in 1995. He is currently the psychiatrist of the Child and Family Guidance Center Northpoint Intensive-Outpatient Day Treatment Center in Northridge, CA. Dr. Pablo Davanzo can be reached by voicemail at his Brentwood office (310) 571-1519.

by PRIDE Reading Program Admin | Mar 6, 2016 | A PRIDE Post, Dyslexia

It may be very frustrating to learn about the importance of early intervention when that window of opportunity has already passed for your middle or high school child with dyslexia. However, acting on behalf of your child will require moving beyond this frustration point and really focusing on what needs to be done in the present. Rest assured that most middle and high school students with dyslexia can be helped and can catch up to grade level. This will take more time, more effort, and more intensity of instruction, but it is never too late to do something about reading and writing difficulties.

Poor readers in middle and high school can be brought up to grade level and kept at grade level with one to two years of instruction using a specialized program intended for students with dyslexia such as the Orton- Gillingham. This approach is multisensory and students use the visual, auditory and kinesthetic channels simultaneously when learning new skills and reading concepts. It is structured, sequential and cumulative.

Students with dyslexia in middle and high school have the same basic problems as younger poor readers and need to learn the same skills. These problems, however, are complicated by years of feeling failure and frustration. Many middle and high school dyslexics no longer believe that they can be helped.

The course of action in helping a child with dyslexia through school may seem like an eternal endeavor to most families, but eventually all the hard work pays off. The dyslexia that caused the child to have difficulties learning to read in the beginning, will also cause troubles later on with spelling, writing, learning a foreign language, and frequently in learning algebra.

Skipping the basic skills of reading is a huge mistake. An older student with dyslexia who lacks basic awareness of speech sounds cannot learn to read unless this problem is addressed. This student will need to begin with phonological awareness, followed by sound-letter correspondences. Unfortunately, there is no shortcut to learning how to decode words fluently and accurately, and no way to bypass this stage altogether of learning to read. Although it is tough in the beginning, nothing is more motivating than success, once students experience appropriate Orton-Gillingham instruction.

A middle and high school student with dyslexia will need an Orton-Gillingham program that is intense enough to close the reading gap. Up to two hours daily may be needed to bring a student to grade level. In general, the larger the gap between the student’s skills and the grade level, the more intense the intervention must be to catch up.

Learn more about the New PRIDE Reading Program

______________________________________________________________________________

Karina Richland is the Founder of Pride Learning Centers, located in Los Angeles and Orange County. Ms. Richland is a Certified reading and learning disability specialist. Ms. Richland speaks frequently to parents, teachers, and professionals on learning differences, and writes for several journals and publications. You can reach her by email at karina@pridelearningcenter.com or visit the Pride Learning Center website at: www.pridelearningcenter.com

by PRIDE Reading Program Admin | Feb 20, 2016 | A PRIDE Post, Auditory Processing Disorder

Almost every school activity, including listening to teachers, interacting with classmates, singing along in music class, following instructions in physical education, etc, depends on the ability for students to process sounds and have a strong auditory system in learning. But what happens if this auditory system has deficits? Can a child still learn?

Does my child have Auditory Processing Disorder?

Auditory Processing (APD) is a very common learning disability and affects about 5% of school-age children. Auditory Processing can present itself with many different symptoms and behaviors. Often these behaviors resemble those seen with other learning challenges, like language difficulties, attention problems and autism. Most children with auditory processing difficulties show only a few of the following behaviors. No child will show all of them. However, any child who displays several of these symptoms should be carefully evaluated for auditory processing disorder.

- Delayed speech.

- Persistent articulation errors.

- Abnormally soft, loud, flat, formal, or “pedantic” speaking voice.

- Difficulty conducting casual conversations.

- Difficulty reading or spelling due to problems discriminating word sounds.

- Difficulty following oral directions.

- Difficulty organizing behaviors.

- A tendency to appear quiet, distracted, or off topic during group discussions or to interrupt or blurt out answers.

- Long delays before responding to questions or instructions.

- Preferences for nonverbal tasks or a markedly higher performance IQ than verbal IQ.

- Difficulty taking notes.

- Worsening performance in higher grades as oral instruction load and receptive language demands increase.

- Difficulties with inference, abstraction, and figurative language.

- Difficulty hearing in the presence of background noise.

- Difficulty understanding what’s said.

- A tendency to ask for restatement or clarification, or repeatedly saying “what?” or “huh?”

- Marked difficulty understanding speakers with particularly high or low-pitched voices or with prominent accents.

How does Auditory Processing affect my child’s learning?

Children with Auditory Processing Disorders have difficulties distinguishing the sounds or phonemes in spoken words, especially those in complex words and sentences. This is referred to as Auditory Discrimination Deficits. If a child has difficulties discriminating sounds in language, then words will sound unclear or distorted as well as many will sound alike. This in turn will affect a child’s development of language skills. They may have trouble speaking and listening, because of problems learning basic grammar and word meanings. Many vowel and consonant sounds may sound the same to them, especially when spoken quickly. As a result, not only will they have difficulty hearing the differences between words that sound alike (think, thing, sink, thin) they will also have difficulty understanding the connections between those words and the letters used to represent them.

This is why children with Auditory Processing Difficulties often have trouble with reading and spelling. Since they cannot hear the sound distinctions between words, the rules linking sounds to letters and letter groups can be hard for them to master.

Most children with Auditory Processing Disorder have difficulty hearing in the presence of background noise. This is referred to as Auditory Figure-Ground Deficits. Although the children often hear well enough at home or in quiet environments, they may appear hard of hearing or even functionally deaf in noisy environments such as school.

In the classroom, a child with Auditory Processing Deficits will have great difficulties staying focused on a listening task. This is referred to as Auditory Attention Deficits. If a teacher is giving a lecture, for example, the student might listen in for a few minutes but then drift off and daydream missing out on significant amounts of information.

Students with Auditory Processing Challenges have great difficulties remembering information given. This is referred to as Auditory Memory Deficits. If the teacher says, “get a piece of paper and a pencil out of your desk and write down your spelling words,” the student may get confused because there are too many commands at once. Impairments in the auditory memory deficits can severely weaken not only long-term memory but also language development and comprehension.

How can a child with Auditory Processing Disorder get help?

The sooner a child with Auditory Processing Disorder is given proper teaching strategies, particularly in the very early grades, the more likely it is that they will have fewer or milder difficulties later in life. These students will need a very structured, systematic, cumulative, repetitive and multisensory teaching method such as the Orton-Gillingham approach. By using a multisensory approach the student will be able to learn using the visual and kinesthetic modalities while simultaneously strengthening the auditory channels.

The best learning environment for a student with auditory processing is always one-to-one with very minimal distractions and outside noises. Students who have severe auditory processing disorder may need an intensive training program to catch up and stay up with the rest of their class. During this intensive training, students will overcome many reading, writing, spelling and comprehension difficulties and learn strategies that will last a lifetime.

Teachers and parents both need to remember that Auditory Processing Disorder is a real condition. The symptoms and behaviors are not within the child’s control. Children with Auditory Processing Disorder are not being defiant or being lazy. A child with Auditory Processing Disorder can go on in life and become just as successful as other classmates.

Learn more about the New PRIDE Reading Program

________________________________________________________________________________________

Karina Richland, M.A. is the Founder of PRIDE Learning Centers, located in Los Angeles and Orange County. Ms. Richland is a certified reading and learning disability specialist. Ms. Richland speaks frequently to parents, teachers, and professionals on learning differences, and writes for several journals and publications. You can reach her by email at karina@pridelearningcenter.com or visit the PRIDE Learning Center website at: www.pridelearningcenter.com

by PRIDE Reading Program Admin | Jan 31, 2016 | A PRIDE Post, Orton-Gillingham

Learning to read in English would be such a simple task if all similar-sounding phonemes were spelled the same. They aren’t. English is such an unfair language with so many iniquitous rules! For most of us, learning to read means memorizing the symbolic code of letter combinations and then using them in new contexts. Many of us just read naturally, understanding that these letter combinations create words and sounds. Linguists call these sounds ‘phonemes.’ Our brains just register the words and are equipped to read three or four words ahead of time. We are also mentally able to pull words apart, separate them into syllables and apply all of those unfair spelling rules easily and logically.

For a student with a reading disability, this process of reading does NOT come naturally. Students with dyslexia, for example, do not use the process of sounding out phonemes (decoding) while reading and applying spelling rules while writing (encoding). Dyslexics, in general, memorize words in entirety and make mental pictures of each word they learn. The predicament with this strategy is that when they get to a word that they are unfamiliar with, they have no coping mechanisms to attack that particular word.

An example of the difficulty for some of us to learn which combination of letters creates which phoneme is the sound of the letter ‘a’ as in the word ‘cake.’ The long ‘a’ sound is written differently in different words, as in baby, ape, sail, play, steak, vein, eight and they. For students with reading disabilities, something interferes with the acquisition of these written phonemes, and in order to learn, these students must be taught how to read in a different way. One such way is using a multi-sensory method.

Students with a reading disability often struggle with auditory and/or visual processing. They have troubles recalling words and how they are pronounced. This means that they do not comprehend the roles that sounds play in words. These students have difficulties rhyming words as well as blending sounds together to form words. These students do not understand or acquire the alphabetic system expected of them in the early years. If a student with a learning difference is given a task that uses just hearing and vision, without drawing upon other senses, this student will be at a disadvantage. When taught with a multi-sensory approach, students will learn alphabetic patterns, phonemes and words by utilizing all pathways – hearing (auditory), seeing (visual), touching (tactile) and moving (kinesthetic).

When learning the vowel combination ‘oa,’ for example, the student might first look at the letter combination on a picture of a GOAT, then close his/her eyes and listen to the sound, then trace the letters in the air while speaking out loud. This combination of listening, looking, and moving around creates a lasting impression for the student as things will connect to each other and become memorable. Using a multi-sensory approach to reading will benefit ALL learners, not just those with reading disabilities.

The other significant component in helping a struggling reader learn to read and write is utilizing an Orton-Gillingham approach. In Orton-Gillingham, the phonemes are introduced in a systematic, sequential and cumulative process. The Orton-Gillingham teacher begins with the most basic elements of the English language. Using repetition and the sequential building blocks of our language, phonemes are taught one at a time. This includes the consonants and sounds of the consonants. By presenting one rule at a time and practicing it until the student can apply it with automaticity and fluency, students have no reading gaps in their word-decoding skills. As the students progress to short vowels, they begin reading and writing sounds in isolation. From there they progress to digraphs, blends and diphthongs.

Students are taught how to listen to words or syllables and break them into individual phonemes. They also take individual sounds and blend them into a word, change the sounds in the words, delete sounds, and compare sounds. For example, “…in the word steak, what is the first sound you hear? What is the vowel combination you hear? What is the last sound you hear? Students are also taught to recognize and manipulate these sounds. “…what sound does the ‘ea’ make in the word steak? Say steak. Say steak again but instead of the ‘st’ say ‘br.’- BREAK!

Every lesson the student learns is in a structured and orderly fashion. The student is taught a skill and doesn’t progress to the next skill until the current lesson is mastered. As students learn new material, they continue to review old material until it is stored into the student’s long-term memory. While learning these skills, students focus on phonemic awareness. There are 181 phonemes or rules in Orton-Gillingham for students to learn. Advanced students will study the rules of English language, syllable patterns, and how to use roots, prefixes, and suffixes to study words. By teaching how to combine the individual letters or sounds and put them together to form words and how to break longer words into smaller pieces, both synthetic and analytic phonics are taught throughout the entire Orton-Gillingham program.

Students with reading disabilities need more structure, repetition and differentiation in their reading instruction. They need to learn basic language sounds and the letters that make them, starting from the very beginning and moving forward in a gradual step by step process. This needs to be delivered in a systematic, sequential and cumulative approach. For all of this to “stick” the students will need to do this by using their eyes, ears, voices, and hands.

Learn more about the New PRIDE Reading Program

__________________________________________________________________________________

Karina Richland, M.A. is the Managing Director of Pride Learning Centers, located in Southern California. Ms. Richland is a reading and learning disability specialist. She speaks frequently to parents, teachers, and professionals on learning differences, and writes for several journals and publications. You can visit the website www.pridelearningcenter.com